Chile

Photos

16 Photos

Per Page:

Filter Categories

All

Filters

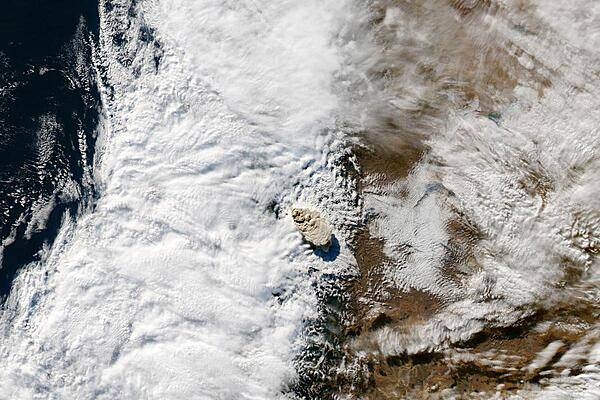

A volcanic ash cloud rises above Chile's Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcano shortly after its eruption on 4 June 2011. Soon after this image was taken, the ash quickly blew eastward towards Argentina. Over the border, near the town of Bariloche, a layer of ash at least 30 cm (12 in) deep covered the ground.

Image courtesy of NASA.

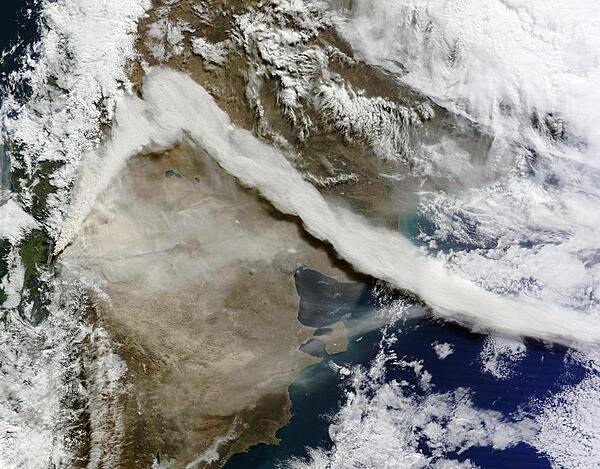

A NASA image taken on the morning of 6 June 2011 shows a large ash plume emanating from Chile's Puyehue-Cordon Caulle volcano. Reaching an altitude of approximately 12,000 - 15,000 m (40,000 - 45,000 ft), the ash cloud drifted north along the Andes. A shift in the prevailing winds then caused the prominent kink visible in the plume. The last major eruption in the Cordon Caulle rift zone occurred in 1960.

Image courtesy of NASA.

Satellite view of the Puyehue-Cordon Volcano Complex on 13 June 2011 - the 10th day of the eruption - shows a very large blanket of ash deposited onto the Pampas of Argentina. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Near the southern tip of South America, a trio of volcanoes lines up perpendicular to the Andes Mountains. The most active is the westernmost, Volcan Villarrica, pictured in this photo-like satellite image. The 2,582-m (9,357-ft) stratovolcano is mantled by a 30-sq km (10-sq mi) glacier field, most of it amassed south and east of the summit in a basin made by a caldera depression. To the east and northeast, the glacier is covered by ash and other volcanic debris, giving it a rumpled, brown look. The western slopes are streaked with innumerable gray-brown gullies, the paths of lava and mudflows (lahars). Beyond the reach of ash and debris deposits, the volcano is surrounded by forests; the area is a national park. The largest recent eruption occurred in the early 1970s; lava flows melted glaciers and generated lahars that spread at speeds of 30-40 km per hour (20-30 mph). Image courtesy of NASA.

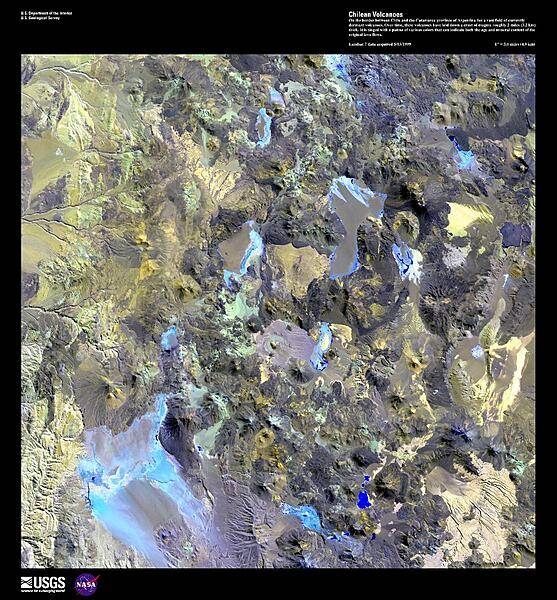

Steep-sided volcanic cones along the Andes on the Chilean-Argentinean border add texture to this false-color satellite image. Of approximately 1,800 volcanoes scattered across this region, 28 are active and form part of the Andean volcanic belt that runs down the length of South America. For more information on other active volcanoes in the region, see the Natural hazards - volcanism subfield in the Geography section under either Chile or Argentina. Image courtesy of USGS.

This panorama looking southeast across the South American continent was taken from the International Space Station almost directly over the Atacama Desert near Chile's Pacific coast. The high plains (3000-5000 m, 13,000-19,000 ft) of the Andes Mountains, also known as the Puna, appear in the foreground, with a line of young volcanoes (dashed line) facing the much lower Atacama Desert (1000-2000 m elevation). Several salt-crusted dry lakes (known as salars in Spanish) occupy the basins between major thrust faults in the Puna. Salar de Arizaro (foreground) is the largest of the dry lakes in this view. The Atlantic Ocean coastline, where Argentina's capital city of Buenos Aires sits along the Río de la Plata, is dimly visible at image top left. Near image center, the transition (solid line) between two distinct geological zones, the Puna and the Sierras Pampeanas, creates a striking landscape contrast. Compared to the Puna, the Sierras Pampeanas mountains are lower in elevation and have fewer young volcanoes. Sharp-crested ridges are separated by wide, low valleys in this region. The Salinas Grandes - ephemeral shallow salt lakes - occupies one of these valleys. The general color change from reds and browns in the foreground to blues and greens in the upper part of the image reflects the major climatic regions: the deserts of the Atacama and Puna versus the grassy plains of central Argentina, where rainfall is sufficient to promote lush prairie grass, known locally as the pampas. The Salinas Grandes mark an intermediate, semiarid region. Image courtesy of NASA.

Brightly colored solar evaporation (salt) ponds in a desert landscape give this astronaut photo an unreal quality. The ponds sit near the foot of a long alluvial fan in the Pampa del Tamarugal, the great hyper-arid inner valley of Chile's Atacama Desert. The alluvial fan sediments are dark brown, and they contrast sharply with tan sediments of the Pampa del Tamarugal.

Nitrates and many other minerals are mined in this region. A few extraction pits and ore dumps are visible at upper left. Iodine is one of the products from mining; it is first extracted by heap leaching. Waste liquids from the iodine plants are dried in the tan and brightly colored evaporation ponds to crystallize nitrate salts for collection. The recovered nitrates are mainly used for fertilizer for higher-value crops. They are also used in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals, explosives, glass, and ceramics, as well as in water treatment and metallurgical processes. Image courtesy of NASA.

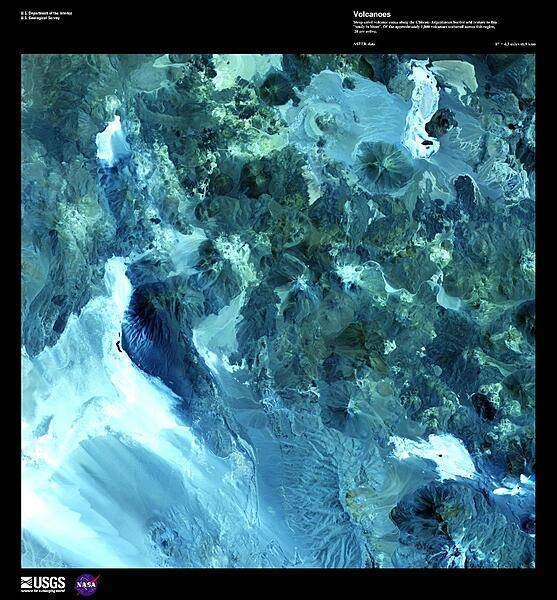

On the border between Chile and the Catamarca province of Argentina lies a vast field of currently dormant volcanoes. Over time, these volcanoes have laid down a crust of magma roughly 3.2 km (2 mi) thick. This enhanced satellite image is tinged with a patina of various colors that can indicate both the age and mineral content of the original lava flows. Some arroyos and alluvial fans may be seen in the upper left portion of the photo. For active volcanoes in Chile and Argentina, see the Natural hazards-volcanism field in the Geography section. Image courtesy of USGS.

Discovered by Dutch sailors on Easter Sunday 1722 and named for the holy day, the isolated Pacific island had already been inhabited for more than one thousand years, most likely settled by Polynesian sailors in canoes between A.D. 400 and 700. The most amazing cultural artifacts on display were giant stone statues, called moai, resting on ahu, raised platforms of expertly fitted stones. Most of the hundreds of moai on the island were carved out of volcanic rock in the crater of Rano Raraku, located in the southeastern part of the island. In addition to the many moai scattered around the coast of the island, Rano Raraku is littered with moai, some only half-carved, others that appear to have broken in the attempt to remove them from the quarry, and still others that seem to simply have been abandoned. East of Rano Raraku is Ahu Tongariki, where in 1960 a tidal wave caused by an earthquake in Chile struck the southern coastline and swept 15 moai inland for several hundred feet. In 1992, the site was restored by a Chilean archeologist. On the western end of the island is the only town, Hanga Roa, where most of Rapa Nui's 2,000 residents live. South of the town is the island's largest volcanic crater, Rana Kao. Along the crater rim looking southward over the coast, lie the ruins of Orongo, a ceremonial site containing elaborate stone carvings and other artwork. Landsat image courtesy of NASA.

View of Easter Island from space. The island is one of the most remote locations on Earth, being more than 3,200 km (2,000 mi) from the closest populations on Tahiti or Chile. The island is perhaps most famous for the giant stone monoliths, known as moai, that have been placed along the coastline. Archaeologists believe the island was discovered and colonized by Polynesians sometime between A.D. 400 and 700. Subsequently, a unique culture developed. The human population grew to levels that could not be sustained by the island. A civil war resulted, and the island's deforestation and ecosystem collapse was nearly complete. Today, a new forest (primarily eucalyptus) has been established in the center of the island (dark green). Less than 25 km (15 mi) long, the geography of the island is dominated by volcanic landforms, including the large crater Rana Kao at the southwest end of the island and a line of cinder cones that stretch north from the central mountain. A final feature (difficult to see) is the very long runway (Chile's longest) near Rana Kao, which served (but was never used) as an emergency landing site for the Space Shuttle. Image courtesy of NASA.

The entrance to Fuerte Bulnes, a Chilean fort located by the Strait of Magellan, 62 km (38 mi) south of Punta Arenas. The fort was originally built in 1843 to encourage colonization in Southern Chile, protect the Strait of Magellan, and ward off claims by other nations. Harsh weather prevented large-scale settlement and in 1848 the government founded Punta Arenas to the north; the fort was abandoned and burned. Between 1941 and 1943, it was reconstructed and in 1968 became a national monument.

Cape Horn, named after a city in the Netherlands, is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago in southern Chile. It is frequently referred to as the "sailors' graveyard" because the waters around the area are particularly hazardous due to strong winds, large waves, strong currents, and icebergs.

Page 01 of 02