For decades, CIA and its Directorate of Science and Technology (DS&T) have been on the forefront of technology. The lithium-iodine battery, advanced medical image-processing techniques, and Google Earth can all be traced back to CIA technical research. Now more than ever, the Agency is focused on the importance of technology in both performing our mission and defending against adversaries.

At CIA, we have looked to our DS&T officers to help us stay ahead of the curve and help solve some of the nation's most vexing challenges. Many call them the "Wizards of Langley"—a fitting moniker for some of the most capable and creative people in the U.S. Government. All around the world, these scientists, engineers, and tech experts work side-by-side with case officers to tackle intelligence problems using cutting-edge technical solutions that help protect the nation. At times, they partner with other Intelligence Community or private sector specialists, but you can be sure they are always pushing the boundaries of state-of-the-art technologies and tradecraft to figure out how to do things nobody else is thinking about or equipped to solve.

We would like to take you on a swift journey outlining the history of CIA's Directorate of Science and Technology, where these outstanding officers work.

* * * * * * * * * *

Science is not everything, but science is very beautiful.

Some of the last published words of Robert Oppenheimer, physicist, in 1966

After WWII ended and the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) grew increasingly at odds, Washington struggled to develop authoritative intelligence assessments, including of the Soviet Union’s atomic research and development (R&D) programs. Even the newly-created CIA in 1947 faced bureaucratic constraints and coordination issues that hampered the work of scientific intelligence.

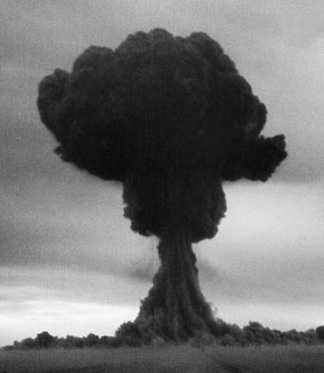

The USSR’s first atomic test, “Joe 1,” August 29, 1949. [Photo from Department of Energy’s Office of Scientific and Technical Information, OSTI.gov]

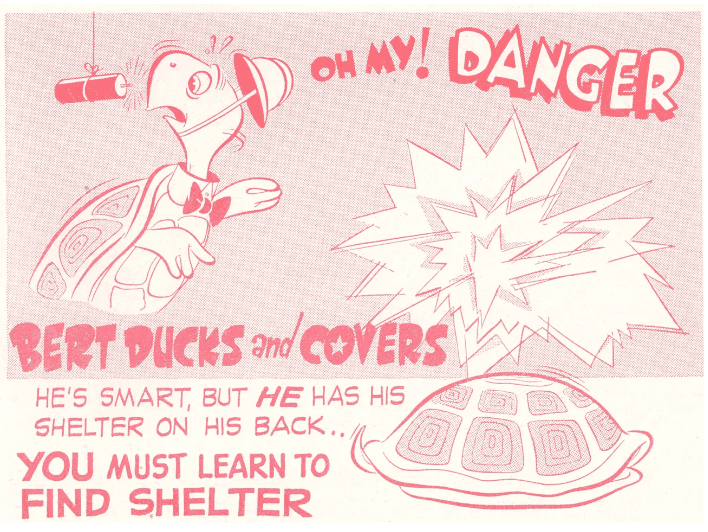

The USSR delivered a sobering wake-up call in late August 1949 when it detonated its first atomic weapon. Four years later, the Soviets tested their first hydrogen bomb, barely nine months after the US first tested such a device. Ambiguity about the size and capabilities of Soviet strategic bomber and missile forces greatly troubled Washington. Policymakers pressed the government to take full advantage of emerging technologies that could defend the homeland and deter a Soviet nuclear first strike. Meanwhile, Americans nationwide prepared for the looming threat.

“Bert the Turtle Says Duck and Cover” pamphlet produced by the Federal Civil Defense Administration, 1951. [Image from National Parks Service, nps.gov via archive.org]

President Eisenhower, over the next several years, sought a full range of views and options to focus the country’s scattered scientific and technological efforts as CIA seniors and military departments with competing priorities continued to wrangle behind the scenes. He met with the Technological Capabilities Panel in 1954. The panel of distinguished experts, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) president James R. Killian and Polaroid Corporation chairman Edwin Land, examined how technology might address the Soviet threat.

Killian and Land argued that the future of intelligence collection rested with the innovations of scientific laboratories in government and the private and academic sectors. In a 190-page report titled Meeting the Threat of Surprise Attack (also known as the Killian Report), the panel urged the creation of a distinct science and technology directorate within CIA that could facilitate crossover among these entities and speed the development of technical collections systems, especially those based in space.

U-2 spy plane after flight at Groom Lake (better known as Area 51), c. 1955-56. [Photo courtesy of TD Barnes and Roadrunners Internationale]

CIA and US Air Force begin developing the CORONA satellite, late 1950s.

In the early 1960s, CIA’s technological achievements in air and space—namely the U-2, A-12, and CORONA photoreconnaissance efforts—as well as the Agency’s R&D programs, scientific analysis, and technical support for operations, convinced many within the US Government and beyond that the Agency needed a separate directorate to manage these enterprises for intelligence purposes.

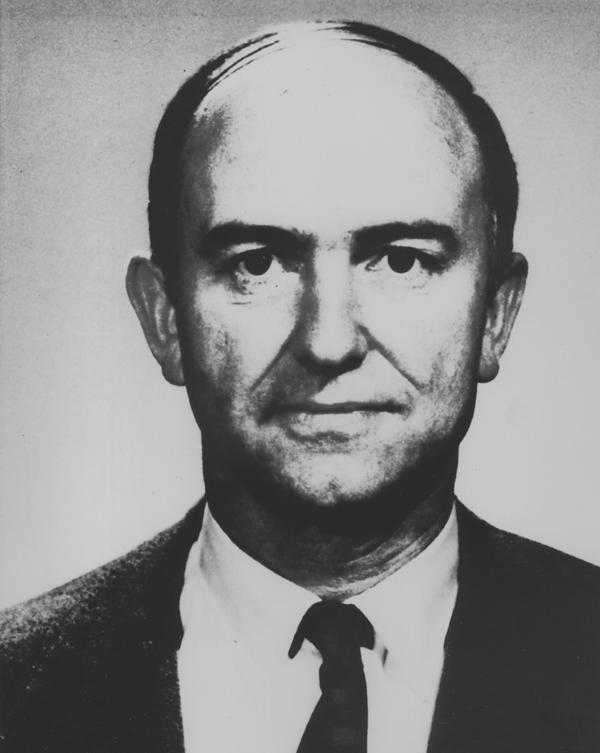

President Kennedy’s pick for Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), John McCone, regarded technical collection as vital to CIA’s future and prioritized the establishment of a new directorate focused on science and technology. He stood up the Directorate of Research in 1962 and tapped analytic manager and former Los Alamos National Laboratory senior scientist Herbert “Peter” Scoville, who had participated on Killian’s panel, to lead it.

Herbert Scoville

Scoville proposed creating an in-house laboratory at CIA for exploring and testing new technologies. He also sought primary responsibility for all things related to science and technology at CIA, but the existing operational and analytical directorates pushed back. As a result, the Directorate of Research did not reach its full potential, and Scoville soon stepped down.

The leadership vacuum left by Scoville was brief but consequential, prompting DCI McCone to decisively re-organize the Agency’s science and technology elements in line with the Killian Report’s vision. After nearly a decade, that goal was finally achieved with the creation of the Directorate of Science and Technology (DS&T) on August 6, 1963.

Technology, its impact on the national security, depends on people.

Bud Wheelon

Albert “Bud” Wheelon, a talented visionary, took on the challenge of becoming the DS&T’s first director and overseeing the Agency’s relevant components. At 34 years old, not only was he adept at navigating the bureaucratic obstacles, he already possessed a physics doctorate from MIT (earned at age 23) and had prior space engineering experience.

“Untouchable,” a mixed media depiction of CIA’s A-12 (U-2’s successor) developed under the highly secret Project OXCART. The very fast, very high-flying reconnaissance aircraft was designed to avoid Soviet defenses. It was declared fully operational in 1964 and first deployed in 1967. [© Dru Blair, artist; “The Art of Intelligence”]

During Bud’s short tenure at CIA, he pushed the Agency forward in science and technology significantly with his contributions. For instance, he led his directorate in successfully employing the U-2 during the Cuban Missile Crisis to contain the nuclear arms race and helped advance the development of the A-12 “Oxcart” (the U-2’s successor). From the outset, Bud indicated he would serve as Director of the DS&T for only three years; he relinquished his role in 1966 and returned to the private sector in his home state of California.

When I first came to CIA... I was always trying to stress that when we do a paper, a delivery, or whatever else, our objective ought to be to sell that idea to the policymaker. Otherwise, what is the purpose of our being here?

Carl Duckett

Carl Duckett, a veteran of WWII and the Korean War, picked up the leadership mantle from Bud after previously serving as his scientific advisor. Before entering the world of intelligence, Carl had studied radio engineering at Johns Hopkins University and went on to work nearly two decades in the civilian and military sectors’ technological and aerospace fields. Though he did not have an advanced degree, Carl was an esteemed expert on missile technology, had an encyclopedic memory, and excelled at conveying complicated scientific ideas and theories into non-technical language and building consensus.

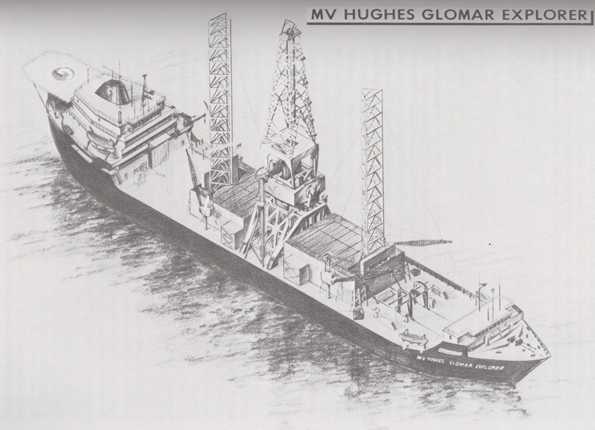

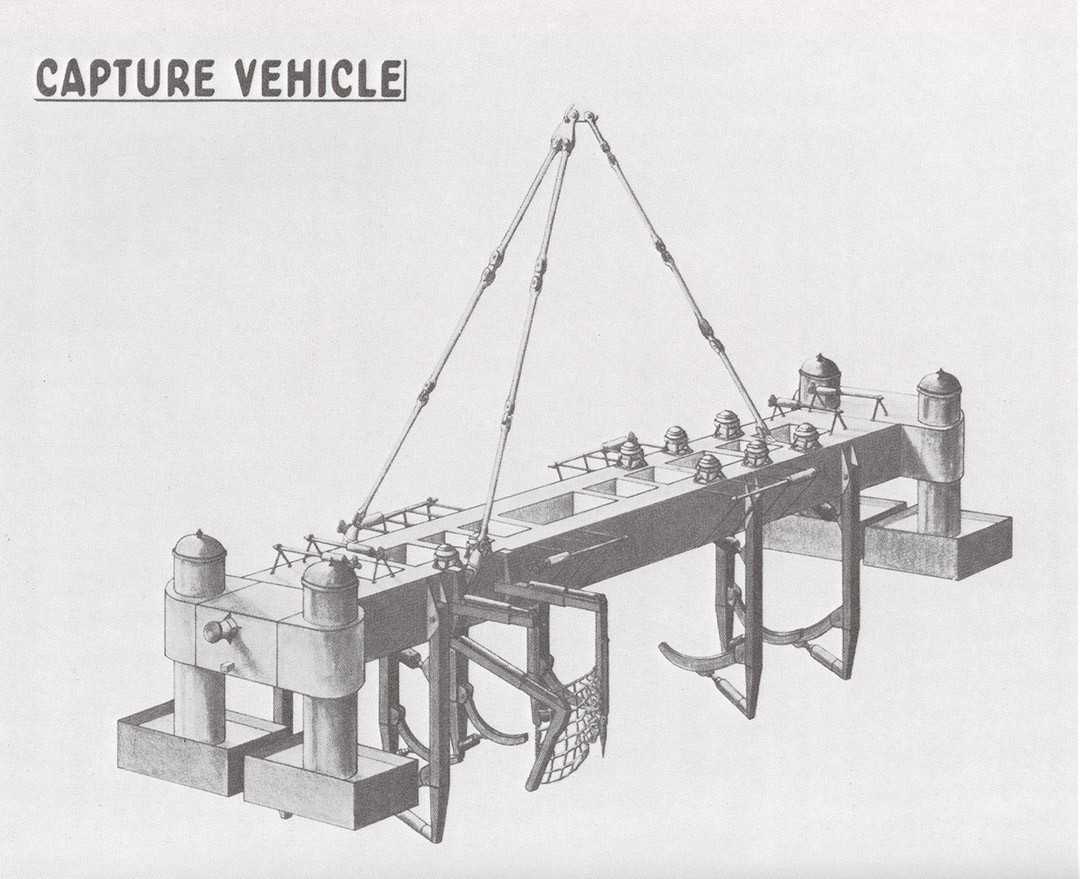

Project AZORIAN. While the public believed the Hughes Glomar Explorer to be a vessel for deep sea mining, CIA was really using the ship to retrieve a sunken Soviet submarine.

Carl firmly established the DS&T’s status and integrated its efforts within the broader Intelligence Community during his 10 years serving as director. During this time, one of his signature accomplishments was his role in advancing the DS&T’s daring mission in 1974 to retrieve a sunken Soviet submarine, which provided key insights into the USSR’s strategic capabilities. Project AZORIAN was an engineering marvel and one of the greatest intelligence triumphs.

The Agency created this custom-made CIA seal to commemorate the success of Project AZORIAN and gave it to Carl Duckett in the early 1970s. It was bequeathed to his colleagues when Carl passed away in 1992.

By the end of the Cold War, the DS&T had designed, built, and deployed technical collection systems that gave the US a significant intelligence advantage over its adversaries.

* * * * * * * * * *

The DS&T’s mission expanded once the Cold War threat subsided, and its officers began to address new threats as well, including those emanating from rogue states and terrorist groups. Of course, most of the work these “wizards” currently do is a closely guarded secret—probably even outside the scope of your imagination. It’s safe to say, however, that they continue to embody a can-do spirit of ingenuity and adapt in response to changes in the world and the evolving technology landscape.

DS&T’s first seal in 1963.

DS&T’s current seal.