Traveling westward during the Great Depression, through the winding Rocky Mountains of Colorado and the high rugged deserts of Arizona, a young Fisher Howe had an inkling he’d someday work in foreign lands. What he didn’t know was that his journey would last 100 years, and during his lifetime he’d not only contribute to the foundations of today’s diplomatic services, but he would also personally witness the formation of America’s first spy agency, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In a talk with CIA historians in 2003, Fisher discussed how he went from being a Harvard graduate, to traveling across the United States selling thread during the Great Depression, to eventually joining the OSS during WWII and serving as a Special Assistant to the famous OSS Director “Wild Bill” Donovan himself.

Coming of Age During the Great Depression

Fisher was born on May 17, 1914, in Winnetka, Illinois. He was one of five children, the son of an investment banker, and was comfortable but not wealthy growing up. The siblings all attended the same North Shore Country Day School (K to 12), and then Fisher and his three brothers went to Harvard, while his sister went to Vassar. They were a close-knit family.

Fisher graduated from Harvard in 1935, earning an A.B. degree in history and literature. He debated whether to go to law school or into business, and ultimately decided on business. A bit of a contrarian, Fisher took the assignments his classmates said they’d never do. No one wanted to go into selling, so of course, that’s exactly what Fisher did. His classmates didn’t want to move west of the Hudson River, so Fisher found a job that would send him to locations all across America.

Fisher started working for the Coats and Clark Thread Company in 1935, where he traveled from New York to places like Colorado, Arizona, Texas, and the Adirondacks selling thread during the Great Depression. The company sent him abroad to work in England and Yorkshire for a year as well. He stayed with Coats and Clark until 1939, when he decided to follow his passion and go into the Diplomatic Service.

Fisher came back to the East Coast to attend “Mr. Turner’s Diplomatic School,” where he took an intensive course for six months in preparation for the Foreign Service exam, which he took in 1940. The exam lasted for three and a half days. He wouldn’t hear back about his results for at least four months, so he moved West again and taught at the Webb School in Claremont, California while awaiting his results. He failed by a few points.

He took the exam a second time in the fall of 1941, but by the time he learned he’d passed, he was already working in London for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

From Thread Salesman to OSS Officer

Fisher arranged meetings with several acquaintances before he even finished taking the Foreign Service exam. Immediately upon leaving the exam site, he had a meeting with someone high up in the Rockefeller Foundation, who worked in an office dealing with Latin American issues.

The Rockefeller Foundation told Fisher they didn’t have any jobs open, but that, “there’s some kind of new agency that’s started over there in the International Trade Building, the Apex Building, on Constitution Avenue. Why don’t you go over there?”

Fisher said he walked over to the office without knowing anything about it. “There was a pretty girl in the downstairs reception,” he recalled. “I asked if I could see the Directory of who was in this agency.”

The woman said, “No, it’s too confidential,’ but then she asked, ‘Where’d you go to college?’ And I said, ‘Harvard.’ ‘Who’d you study under?’ And I named a few professors, and when I came to James Phinney Baxter, ‘Oh, did you want an appointment with Mr. Baxter… with Professor Baxter?’

Around the same time, Fisher’s father asked him to make a courtesy call on a family friend, Ralph Bard, who happened to be Assistant Secretary of the Navy. By chance, Fisher mentioned to Bard that he had applied to an agency, Coordinator of Information (COI), although he didn’t know anything about the organization. Bard didn’t say a word, but apparently that night he had dinner with General William J. Donovan. The next morning, Fisher got a call from the COI Director’s office saying, “You are now Special Assistant to the Director, Mr. Wild Bill Donovan.”

That’s how Fisher came to work for the OSS, although, at the time, it was still called the Coordinator of Information. It would be another four-to-five months before the COI became the OSS.

Working for “Wild Bill”

Fisher gave an interview on February 3, 1998, for the Foreign Affairs Oral History Project as part of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. In the interview, he discussed his impressions of “Wild Bill” Donovan.

“He was great as a leader,” recalled Fisher. “He attracted loyalty from a wide number of very prominent, very effective people.” Fisher explained that Donovan was very close to President Franklin Roosevelt, but because he was “a hard driving operator” in government circles, a lot of people in Washington resented Donovan’s close ties with the President. “And he was totally dependent on those ties,” said Fisher.

Although Fisher thought highly of Donovan, he also described the OSS Director as “irresponsibly adventuresome.” For example, “Donovan spent a lot of time — more time than he should have — down in Cairo mounting these operations… He knew that [The Battle of Midway against the Japanese] was going to take place, so he was at Midway. He was on the boats landing across the channel [in the Pacific Theater]. He was right in the Mediterranean whenever there was anything there and doing things that no head of intelligence should have been doing.”

Nevertheless, Fisher, in an article he wrote for the OSS Society, said he admired Donovan’s leadership and considered him a friend. “The word exude is to display abundantly…General Bill Donovan exuded charm and power. His soft blue eyes were warm and friendly, but they had a steely quality. If you define leadership as, ‘to have a vision for an organization and the ability to attract, motivate, and guide followers to achieve that vision,’ you have General Donovan the leader—in spades! He knew everyone, everywhere—in all walks of life—and he charmed them into joining him in his mission and then led them in action. Lots of action.”

“If you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate, and guide followers to fulfill that vision, you have Bill Donovan in spades.”

Special Assistant to "Wild Bill" Donovan

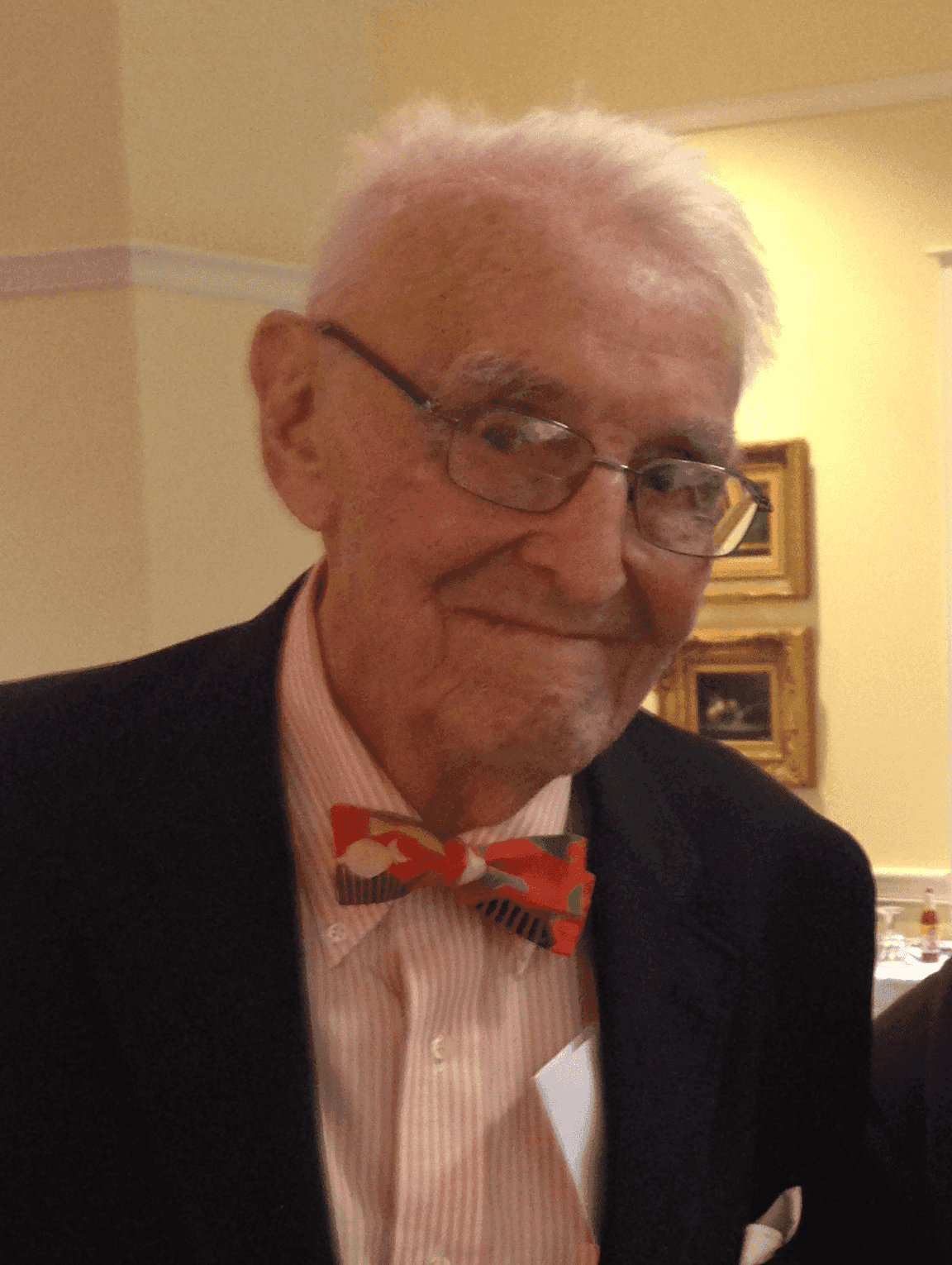

Fisher Howe

Those who worked closely with Donovan, said Fisher, knew him as a difficult, demanding, inspiring, and rewarding leader. A warm companion. “Do we dare say friend?”

Fisher, along with two colleagues, became Donovan’s special assistants. They met with him at the end of every day to parcel out assignments and follow up on Donovan’s many hectic activities. “He would then go off to a power dinner to make more friends and glean more information from Washington’s wartime establishment,” said Fisher.

Donovan then asked Fisher to become the Executive Director of the OSS station in London. “I was in the Embassy,” Fisher told CIA Historians, “and doing the liaison with British Intelligence, SOE, MI-5, MI-6… although MI-6 at that point was not very friendly, or, at least, was not very cooperative.”

When Donovan came to London after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he was traveling alone, so he needed an aide. Fisher moved in to Donovan’s Claridge’s Hotel suite to be his “aide de camp” or personal assistant. Fisher, in his OSS Society article, recalled, “There [Donovan] received Britain’s government elite, marshaled by all-powerful William “Little Bill” Stephenson—the British Intelligence chief in the US who guided the COI/OSS in its early days.”

Fisher would also accompany Donovan on shopping trips. “A hasty shopping trip — not a stroll — along Bond Street to buy an array of books — he could read one or two in an evening — and gifts for Ruth [his wife] and loyal Washington staff members.” Fisher joked that, “Someone had to go along to pay — he carried no money himself — and lug the armful.”

While in London, Fisher learned he had passed the written part of the Foreign Service exam, so Donovan arranged to fly him back to the US on a bomber airplane to take the oral exams. Fisher passed, and was told by the Foreign Service that he would resign from the OSS and become Vice Consul in Guayaquil.

“I said, ‘No way.’ I had a prime job in London and was not going to move.” The Foreign Service refused to give him a position working with the OSS in London, so despite passing the exams, Fisher never joined.

In London, Fisher helped set up the OSS headquarters. Donovan then told Fisher he needed to get some military service under his belt. Fisher had previously been denied because he was asthmatic. Donovan asked Fisher, “Which service do you want?” and he said, “Navy.” Donovan made a phone call and three weeks later, Fisher became a Lieutenant in the United States Naval Reserves.

He was immediately assigned back to the OSS, where he received parachute and small boat training for various infiltration missions into Italian and German territories. Fisher ended up traveling from London, to the Mediterranean, and then to India and Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) for the OSS.

In Ceylon in 1944, Fisher ended up developing bronchial pneumonia and was flown back to the US for treatment. Penicillin had recently been produced for medical treatment, but supplies were scarce and the drug was still relatively new. Nevertheless, Fisher received one of the early doses and spent the next two months recovering at Bethesda Naval Hospital. He was confined to an oxygen tent, and then the doctors told him he had to move West, because of the higher-altitudes and drier air, for at least six months to finish his recovery.

“I went out to teach… I hitchhiked to a school,” recalled Fisher. “It was a beautiful boys’ boarding school, a ranch school. Three days later, I ran into the headmaster’s daughter. We courted, and three days after commencement, we were married.”

Fisher and his new bride returned to Washington, and in June of 1945, Fisher once again became Donovan’s Special Assistant, although his tenure would be short. The war was over and President Truman was in the process of disbanding the OSS, which was officially dissolved on October 1, 1945.

The Nine Lives of Fisher Howe

When the OSS was disbanded, Research and Analysis went to the State Department, while Espionage and Counterintelligence became part of the newly created Strategic Services Unit (SSU).

In 1946, President Truman created the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), which absorbed the SSU, and in 1947, Truman signed into law the National Security Act, the legal basis for the CIG to officially become the Central Intelligence Agency.

It was in the middle of this transition period, in 1946, that Fisher joined the State Department as a Special Assistant to Will Clayton, the Under Secretary for Economic Affairs. Although Fisher never served in the CIA, he still worked closely with his colleagues in the Agency. In 1948, Fisher became deputy head of intelligence for the State Department, serving under Park Armstrong.

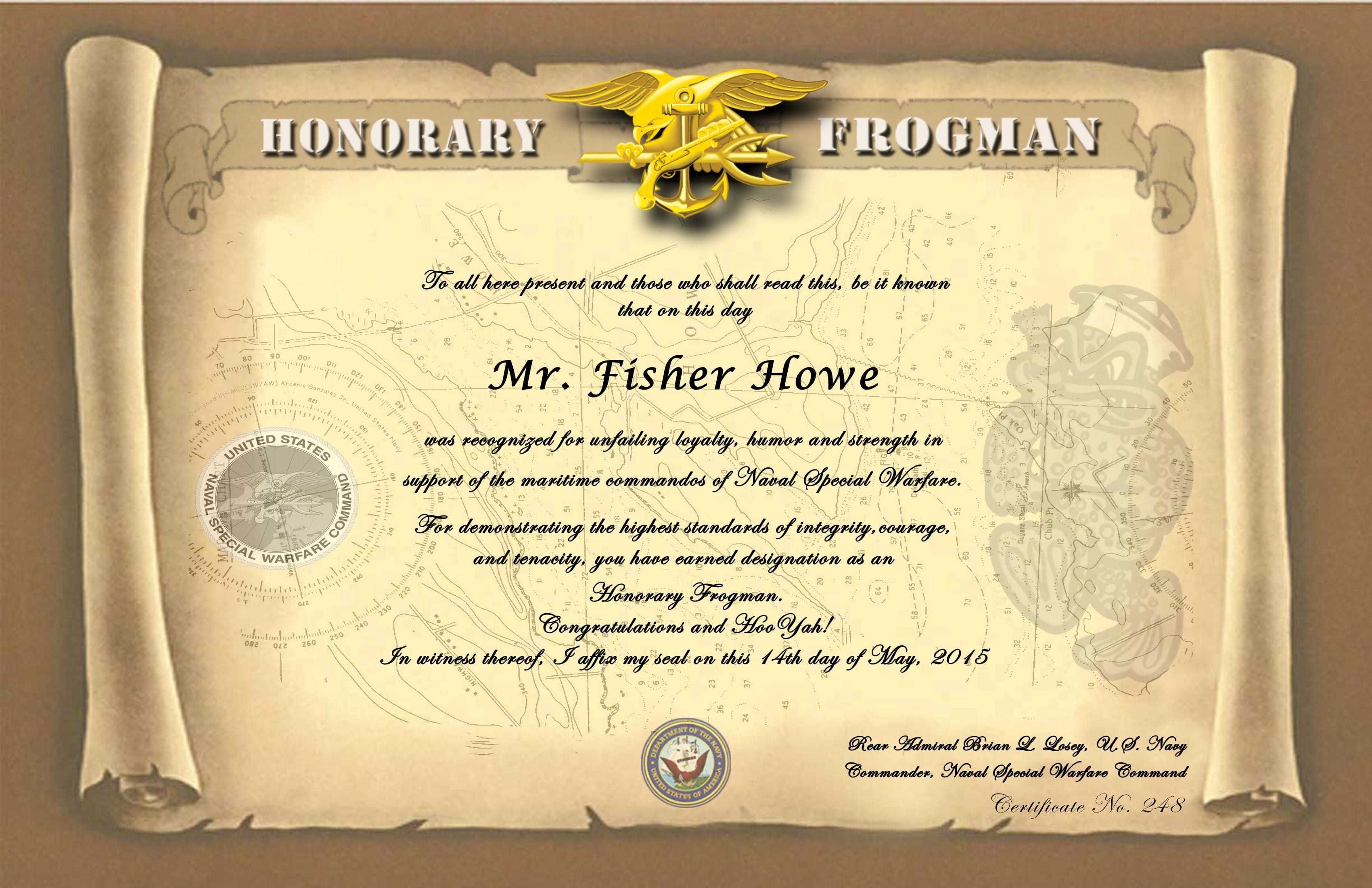

Admiral Brian Losey, USN, Commander, Naval Special Warfare Command, planned to present this certificate to Fisher at this year’s William J. Donovan Award Dinner on November 7, 2015. Courtesy of OSS Society.

Because of Fisher’s background in the OSS and now the State Department, he understood both the Intelligence and Foreign Service worlds. He tried to help the organizations navigate their complicated relationships and changing missions.

In 1950, the National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) was created as a collective Intelligence Community assessment on particular national security issues and future outcomes. Fisher had an opportunity to brief the NIE to senior policymakers and was once asked, “What good are those NIEs when they compromise all the language, and so you get something that’s bland?” He didn’t have a good answer at the time, but from that day forward, Fisher knew exactly what he would say if ever asked again:

“Mr. Secretary, you will get a view that is the view of every intelligence agency, even if it’s bland. You will not get five different views as to what the situation is, because you’ve got one that they’ve had to agree to. It keeps you from having to be the coordinator of separate Estimates.”

Fisher worked for the State Department until 1968, after which he became an assistant dean at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

In the late 1970s, he became director of external relations at Resources for the Future, a nonprofit dedicated to issues involving the environment, natural resources, and energy policy. He eventually “retired” as a management consultant for nonprofit organizations, and he also wrote several books on nonprofit management and fundraising.

In his spare time, Fisher took up tennis. Never one to go lightly, he placed third nationally in his US age group: He was well into his 90s at the time.

In 2009, when Fisher was 94, a coronary bypass surgery he had 20 years prior began to fail. His physicians told him he was clearly not a candidate for another surgery given his age, but Fisher, not afraid to politely challenge conventional wisdom, wouldn’t accept that. He convinced doctors at Johns Hopkins Medical Center that he could make it through the surgery. “My goal,” Fisher said, “is to make it to 100.”

And he did just that. On May 10, 2015, Fisher Howe died at his home in Washington, just shy of his 101st birthday.