Less than three years after its creation, the CIA became involved in its first “hot war” after North Korea launched an invasion of South Korea on June 25, 1950. The new Agency conducted an array of espionage and covert operations unilaterally and in support of US Armed Forces taking part in a UN coalition.

The most persistent controversy about the CIA and the Korean War concerns whether the Agency warned US policymakers that North Korea would attack its southern neighbor. As is typical in situations involving warning, the reality is complex, and a collection of declassified CIA documents help dispel widely held assertions that the Agency committed a serious intelligence failure.

Caught By Surprise?

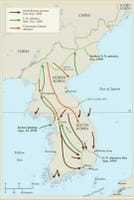

On Sunday June 25, 1950, Communist North Korean troops, supported by Soviet-supplied tanks, heavy artillery, and aircraft, crossed the 38th parallel and invaded the Republic of South Korea. Notified at his home in Independence, MO, by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, President Harry Truman acted quickly and decisively, instructing Acheson to contact the UN to seek a resolution condemning the invasion and aid in the effort to provide assistance to South Korea.

By all appearances, the North Korean attack seemed to have caught the Truman Administration, the US Army’s Far Eastern Command under Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, and the fledgling CIA by surprise. Within days, administration and congressional critics charged that the Agency did not fulfill its primary mission of providing warning to the president, an intelligence failure of the highest magnitude.

Did the Agency Provide Tangible Intelligence?

Critics of the CIA before and after the Korean invasion focused on the relatively few references to Korea in intelligence reporting. In particular, they noted the lack of any predictive estimates or other “actionable” warning intelligence that would have allowed US policymakers to anticipate Korean events before they reached the crisis stage.

Yet, contrary to what historians have written for many decades, CIA analysts did report frequently on Korea in the prewar years, although from a perspective that highlighted the Soviet Union’s involvement rather than local Korean events. At the time, America viewed the communist movements around the world as being controlled from the Kremlin. Therefore, events in Korea were seen as just one of many fronts in the Cold War, closely interrelated with other Soviet-induced crises but not of any greater or lesser importance.

While analysts consistently and accurately provided current intelligence on Korean developments, the reports did not emphasize that the increasingly dangerous situation there represented anything extraordinary beyond routine Soviet mischief-making and proxy-sponsored “tests” of American resolve.

The Agency’s Office of Research and Reports did, however, provide ominous predictions and indicated the possibility of some regional crises from 1947 through 1950. But in a world menaced by communists everywhere, CIA reporting on Korea did not stand out either in intelligence publications or in the minds of policymakers.

The CIA in 1950:

CIA was a small organization in 1950 and lacked a robust collection and analytical capability. Formed by the National Security Act of 1947, it had only 5,000 employees worldwide in late January 1950, with just 1,000 of them employed as analysts and only three operations officers in Korea before the June 1950 invasion.

Overwhelmingly, analytic products that did appear came in the form of current intelligence, which filled lower-level customer demands but did not meet high-level policymaker needs and reflected the generally low priority given to the Far East then by the State Department and the military services.

Intelligence Leading Up to the Invasion:

Starting in 1949, CIA reporting on the potential for war in Korea became more explicit, especially as long-sought military proposals for withdrawing US forces from the peninsula came closer to reality. CIA warned that removing US troops would likely lead to war.

The CIA’s Office of Reports and Estimates (ORE, a predecessor to the Directorate of Intelligence, now known as the Directorate of Analysis) put together a series of reports on Korea, which often appeared in the periodic, monthly assessment of current intelligence reporting called, “The Review of the World Situation As It Relates to the Security of the United States.”

Once such ORE report from February 28, 1949 (ORE 3-49) titled, “Consequences of US Troop Withdrawal from Korea in Spring, 1949,” stated, “In the absence of US troops, it is highly probable that northern Korean alone, or northern Koreans assisted by other Communists, would invade southern Korea and subsequently call upon the USSR for assistance. Soviet control or occupation of Southern Korea would be the result.”

The reported concluded that, “withdrawal of US forces from Korea in the spring of 1949 would probably in time be followed by an invasion, timed to coincide with Communist-led South Korean revolts, by the North Korean People’s Army possibly assisted by small battle-trained units from Communist Manchuria….US troop withdrawal would probably result in a collapse of the US-supported Republic of Korea.”

In the spring and summer of 1950, reports from ORE reaching US military headquarters in Japan and top policymakers in Washington indicated the probability of trouble ahead, although these assessments as before were vague and by no means explicit.

On January 13, 1950, CIA noted, “A continuing southward movement of the expanding [North] Korean People’s Army toward the thirty-eighth parallel” and their acquisition of heavy equipment and armor but did not see an invasion as imminent. Still, the Review contained little information that could conceivably be termed indications and warning of a pending North Korean attack.

The Invasion:

ORE’s next intelligence estimate specifically on Korea appeared just one week before the invasion.

Entitled “Current Capabilities of the Northern Korean Regime,” it declared that North Korea possessed a military superiority over the south and was fully capable of pursuing, “its main external aim of extending control over southern Korea.”

While recognizing “the present program of propaganda, infiltration, sabotage, subversion, and guerrilla operations against southern Korea” did not indicate war was imminent, Agency analysts did note the massing of North Korean forces, including tanks and heavy artillery, along the 38th parallel and the evacuation of civilians from these areas.

While CIA had provided strategic warning of the possibility of an invasion, tactical warning of a specific date, time, and place remained lacking—as critics were later quick to note.

CIA’s Response:

In the days following the outbreak of war, CIA’s analytical offices dramatically increased their reporting on the conflict, preparing a Daily Korean Summary that reported military developments and related international diplomatic and political events directly to the president and national command authorities.

The first issue appeared on June 26, 1950, one day after the war started. Soon after, a special staff within ORE was created to monitor and report solely on Korean events.

Yet to many, CIA had failed, demonstrating that its analytical capabilities were not sufficient, especially now with the nation at war. During the next two years the Agency underwent major organizational changes and hired additional personnel to remedy any real or alleged deficiencies, resulting in a generally larger CIA and a new Directorate of Intelligence created in early 1952.