In April 1961, more than a thousand Cuban exiles stormed the beaches at the Bay of Pigs, Cuba, intending to ignite an uprising that would overthrow the government of Fidel Castro.

Many people know the story of the failed Bay of Pigs operation, but you might not know all the details. Let’s take a closer look at the events that unfolded and at the key players whose covert performances played out for all the world to see.

Descent from the Mountains

In the 1950s, a young, charismatic Cuban nationalist named Fidel Castro led a guerrilla army against the forces of General Fulgencio Batista from a base camp deep within the Sierra Maestra Mountains, the largest mountain range in Cuba. Castro’s goal was to overthrow Batista, the US-backed leader of Cuba.

After three years of guerrilla warfare, Castro and his ragtag army descended from the mountains and entered Havana on January 1, 1959, forcing Batista to flee the country. Castro took control of the Cuban Government’s 30,000-man army and declared himself Prime Minister.

For nearly 50 years, Cuba had been America’s playground and agricultural center. Many wealthy Americans lived in Cuba and had established thriving businesses there. In fact, a significant portion of Cuba’s sugar plantations were owned by North Americans. With Castro’s self-appointment to Prime Minister, that changed.

In February 1960, Cuba signed an agreement to buy oil from the Soviet Union. When the US-owned refineries in the country refused to process the oil, Castro seized the firms, and the US broke off diplomatic relations with the Cuban regime. To the chagrin of the Eisenhower administration, Castro established increasingly close ties with the Soviet Union while delivering fiery condemnations of the US.

The American-Cuban relationship deteriorated further when Castro established diplomatic relations with our Cold War rival, the Soviet Union. Castro and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev signed a series of pacts that resulted in large deliveries of economic and military aid in 1960. Within a year, Castro proclaimed himself a communist, formally allied his country with the Soviet Union, and seized remaining American and foreign-owned assets.

The establishment of a Communist state 90 miles off the coast of Florida raised obvious security concerns in Washington and did not sit well with President Eisenhower.

Eisenhower authorized the CIA to conduct a covert operation to rid the island of its self-appointed leader. The CIA formulated a plan to recruit Cuban exiles living in the Miami area. It would train and equip the exiles to infiltrate Cuba and start a revolution to ignite an uprising across the island and overthrow Castro.

At least that was the intended outcome.

Top US Government officials watched as their decisions led to an entirely different outcome: one that would leave a covert operation exposed, embarrass the new Kennedy administration, end the career of the longest serving Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles, and, ultimately, leave Fidel Castro in power for decades to come.

The Recruits

In April 1960, several CIA officers traveled to Miami, Florida. They were searching for members of the Frente Revolucionario Democratico (FRD), an active group of Cuban exiles who had fled Cuba when Castro took power. These revolutionaries were the ideal individuals to lead an uprising in Cuba, and the CIA, operating with a $13 million budget, recruited 1,400 of them to form Brigade 2506.

The Brigade was taken to Useppa Island, a private island off the coast of Florida that was secretly leased by the CIA.

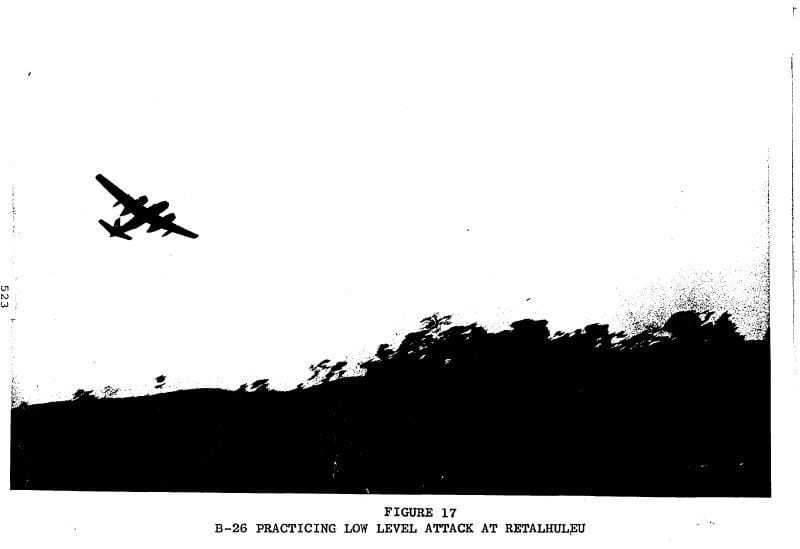

Once there, they received training in weapons, infantry tactics, land navigation, amphibious assault tactics, team guerrilla operations, and paratrooping. Their instructors were from the Army Special Forces, Air Force, Air National Guard, and the CIA. Thirty-nine of the recruits were pilots who had flown in Cuba’s military or as commercial pilots. The pilots were trained at an air training base in Guatemala.

Unbeknownst to the trainers, although likely suspected, sprinkled amongst the recruits were double-agents, working in tandem for Castro, sharing the intelligence that they collected on the upcoming invasion.

The Plan

For simplicity, the Bay of Pigs invasion plan can be broken down into three phases:

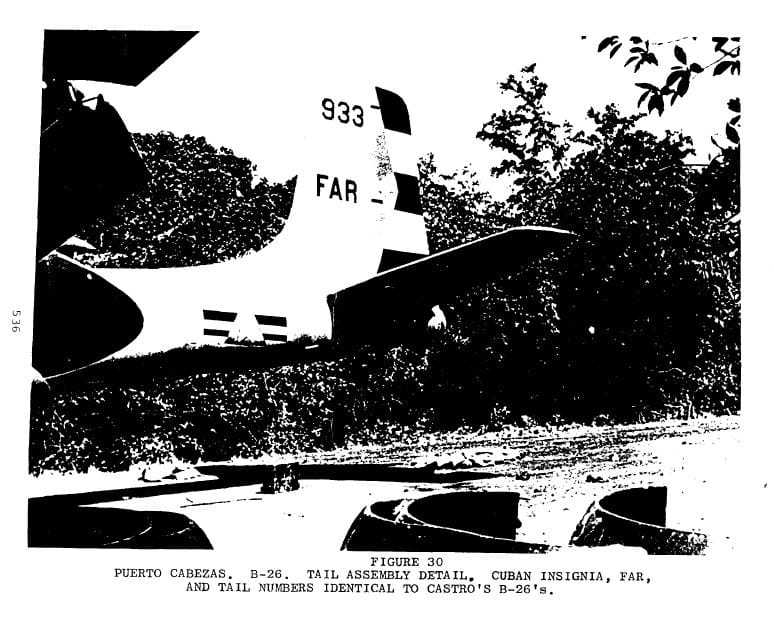

Phase One: Destroy as many of Castro’s combat aircraft as possible so that when the Brigade invaded the beach, Castro’s air force would have no retaliatory capabilities. To do this, pilots of Brigade 2506 planned to bomb three of Castro’s air force bases. The cover story for these bombings was simple. Pilots in the Brigade would pose as pilots in the Fuerza Aerea Revolucionaria (FAR), Castro’s Air Force. Allegedly, they would become disgruntled, take their aircrafts, shoot up their own air force bases, and then fly to the US to defect. This first airstrike was supposed to take place two days prior to the invasion (phase three).

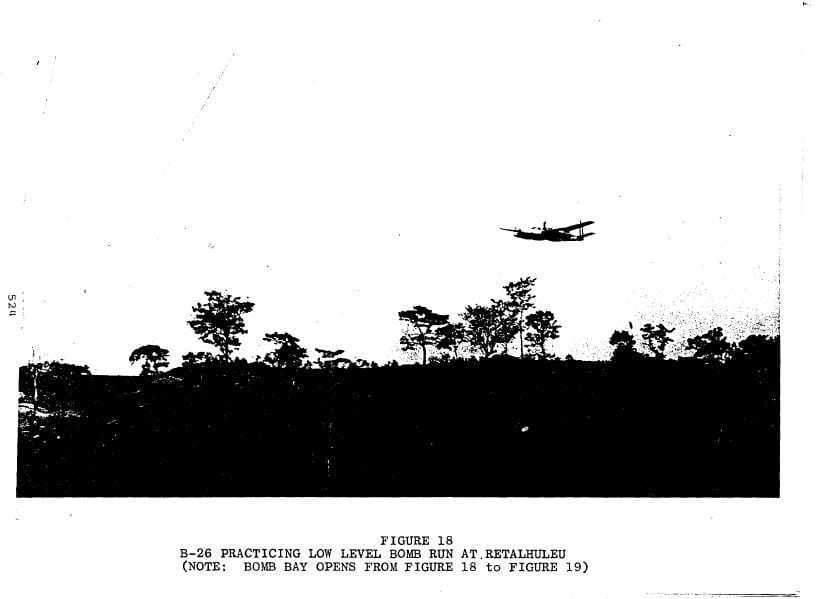

Phase Two: Destroy any remaining combat planes in Castro’s fleet that weren’t taken out during phase one. Pilots in Brigade 2506 planned to drop bombs on Castro’s air force bases in the morning hours prior to the main invasion (phase three) to destroy any remaining combat planes in Castro’s fleet. This would ensure the Brigade members invading the beach would not have to contend with Castro’s aircraft dropping bombs and firing mercilessly on them from above during the actual invasion.

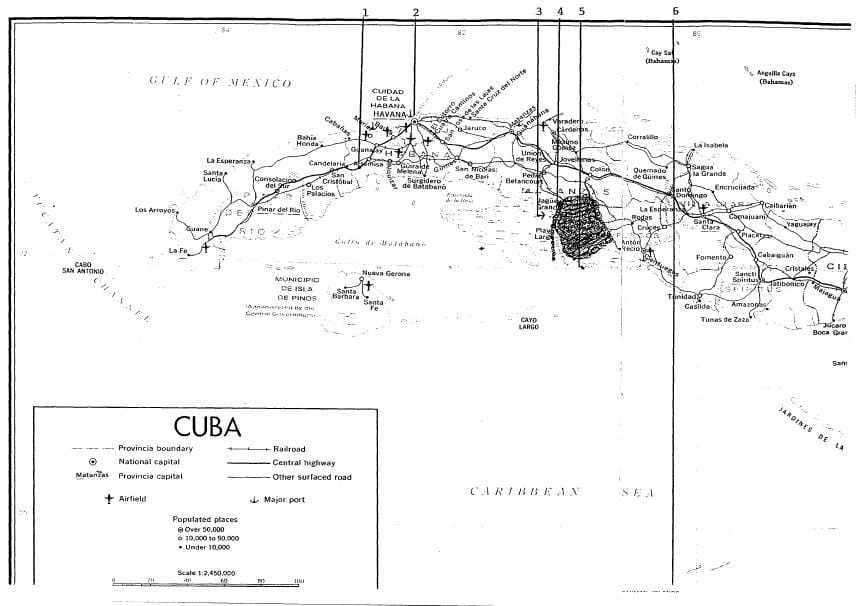

Phase Three: The invasion. The Brigade would invade Cuba by sea and air. Some members would invade Cuba on the beaches of Trinidad; others would parachute in farther inland. The Brigade pilots would fly air cover missions over the beach. The old colonial city of Trinidad was chosen as the invasion site because it offered many significant features. It was an anti-Castro town with existing counter-revolutionary groups. It had good port facilities. The beachhead was easily defensible and, should the Brigade need to execute their escape plan, the Escambray Mountains were there to offer solitude.

Location, Location, Location

As the number of days till the invasion shortened, Kennedy’s concern that the operation would not remain covert grew. He was adamant the hand of the US Government remain hidden at all costs. Kennedy thought changing the invasion site from Trinidad would make future deniability of US involvement more plausible, so he gave the CIA four days to come up with a new one.

And so, a month before the operation was set to get underway, the landing location changed from Trinidad to the Bay of Pigs.

This presented an array of problems, namely, the Bay of Pigs was one of Castro’s favorite fishing holes. He knew the land like the back of his hand. He vacationed there frequently and invested in the Cuban peasants surrounding the bay, garnering their loyalty and admiration.

Additionally, the Escambray Mountains, the designated escape site, was 50 miles away through hostile territory. The bay was also far from large groups of civilians, a necessary commodity for instigating an uprising, which may be a moot point, as the bay was surrounded by the largest swamp in Cuba, making it physically impossible for any Cubans wanting to join the revolt to actually do so.

The Operation Begins

Phase One, April 15: Early on the morning of April 15, phase one was deployed. Six Cuban-piloted B-26 bombers struck two airfields, three military bases, and Antonio Maceo Airport in an attempt to destroy the Cuban air force. Their planes had been refurbished to match those of the FAR; each equipped with bombs, rockets and machine guns.

About 90 minutes later a “defecting” pilot, a member of Brigade 2506, took off in his American-made getaway plane, also disguised as a FAR aircraft. His plane, however, received extra attention. Dirt was rubbed on the markings to make it look worn. A phony flight log was in the cockpit along with various other items typically found in Cuban military aircraft. Finally, because a defector shooting up his own base would most likely encounter resistance, his plane was shot full of bullet holes.

B-26 disguised to look like Cuban aircraft.

The “defector’s” destination was the Miami International Airport. He radioed a “may day” distress signal from off the coast of Florida and informed US authorities that he was defecting from the Cuban Air Force, having engine trouble, and requested permission to land. Upon landing, he was taken into custody by US Customs and Immigration and Naturalization.

Reciting his cover story, he explained that he was defecting from Cuba, but before doing so had attacked his own air base and that two colleagues had also defected and had attacked other Cuban air bases.

Damage assessments of the airstrikes vary, but it is believed that 80 percent of Castro’s combat aircraft were disabled. Assuming Castro had an inventory of as many as 30 combat aircraft, that left six functioning aircraft available at his disposal on the day of the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Castro vehemently denied that the attacks on his airfields had been by rebellious members of the FAR and immediately blamed the US. He also quickly concluded that these strikes were an indication of something larger brewing. He preemptively rounded up thousands of potential dissidents and herded them into theatres, stadiums and military bases to squelch the possibility of a spontaneous uprising to overthrow his regime.

Following Castro’s orders, Raul Roa, the Cuban Foreign Minister, called an emergency session of the United Nations Political and Security Committee in New York on the afternoon of April 15. The session was attended by US Ambassador to the UN, Adlai Stevenson.

Stevenson held up pictures of the planes as he adamantly stated the US had nothing to do with the airstrikes. He insisted that the attacks were conducted by defectors from Castro’s own air force. The pictures, however, proved to be the unraveling of the cover story.

On close inspection, one could make out a metal nose on the plane flown by the defector; FAR aircraft noses were plastic. Ambassador Stevenson, who was unaware of the covert operation, was furious when the truth was revealed.

Cancel the Strikes!

Phase Two, April 16: This was bad news for President Kennedy whose number one priority was hiding the hand of the US Government, which was becoming more exposed as the operation proceeded. Lying to the UN had serious consequences and a second strike would put the United States in an awkward position internationally. Political considerations trumped the military importance of a “D-Day” air strike.

Late in the evening of April 16, Kennedy made the decision to cancel the air strikes set to destroy the remaining fleet of Cuban bombers. The decision was so last minute that the Brigade pilots were sitting on the runway, taxied in position for takeoff when they were told to stand down.

Ironically, however, the air support scheduled to provide cover to the invading Brigade on the beach could proceed as planned. This last minute cancellation forced leadership to work furiously through the midnight hours, reworking and revising their plans, racing the sun as it climbed into a cloudless sky the morning of April 17, 1961: D-Day.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

Phase Three, April 17: The Bay of Pigs invasion began with the launch of eight pairs of aircraft flown by Brigade pilots over the Bay of Pigs. But, like all else, that number too had been scaled back at the last minute, which left large patches of time when no aircraft would be providing air support for the invading Brigade.

The FAR had read the remnants of the April 15 strikes like tea leaves and correctly predicted a second attack. This time, they were prepared.

As the sun’s orange rays stretched across the Caribbean Sea, the members of Brigade 2506 prepared to return home. Not as citizens, not as vacationers, but as invaders. As their vessels drew ever nearer to shore, they saw their island as never before: not as a warm, welcoming place, but as a hostile, yet, strangely familiar territory.

They had been training for this moment, anticipating it and envisioning it for the past year. Now it was upon them. This was their opportunity to make a difference in the country in which they had lived, the country which they had loved, the country from which they had fled. This was their chance to turn the tide.

Yet, it was an ocean tide and unforeseen coral reefs that made it increasingly difficult for the Brigade to even reach the shore. Most of the men lost their weapons and equipment to the turquoise waters.

Once ashore, they were met instantly by Cuban armed forces who outnumbered them. The salvaged and undamaged Cuban planes that had survived the April 15 strikes, the very planes that should have been destroyed that morning had Kennedy not canceled the planned strike, were now flying overhead wreaking mayhem on the Brigade.

The invasion did not go as planned, and the exiles soon found themselves outgunned, outmanned, outnumbered and outplanned by Castro’s troops.

Castro’s first priority was sinking the ships that invaded Cuban waters. The USS Houston, an American troop and supply vessel, was damaged by several FAR rockets, its captain then intentionally beached it on the western side of the bay. The FAR also machine gunned the two landing craft and other supply vessels that had brought the Brigade into the Bay of Pigs. They hit the USS Rio Escondido, which was loaded with aviation fuel, causing a terrific explosion before it sank like a stone.

Meanwhile, the paratroopers dropped in. One set missed their target and lost most of their equipment, and two other men were injured when their static line cable broke. A portion of the equipment that was airdropped sank in the swamps.

The Brigade did have some successes. Several paratroopers hit their targets and were able to hold their positions and block roads for two days. The Brigade pilots providing air cover support successfully destroyed tanks and other armor and halted an advancement of Cuban militia cadets.

Neither side made any significant advances as the invasion and fighting continued into the third day.

The Situation Falters:

The deteriorating operation convinced President Kennedy to authorize six unmarked fighter jets from the aircraft carrier USS Essex to provide combat air patrol for the Brigade’s aircraft for one hour on April 19. But not without strict limitations; they could not instigate air combat or attack ground targets. Limitations, however, wasn’t the biggest problem: timing was.

Somewhere, among the last minute changes and cables going back and forth, there was a miscommunication. As the six jets sat on deck awaiting their scheduled departure time, the Brigade’s aircraft flew over them an hour ahead of schedule. The jets immediately launched after them, but they were unable to reach the invasion area in time to protect the Brigade’s aircraft.

Brigade 2506’s pleas for air and naval support were refused at the highest US Government levels, although several CIA contract pilots dropped munitions and supplies, resulting in the deaths of four of them: Pete Ray, Leo Baker, Riley Shamburger, and Wade Gray.

Kennedy refused to authorize any extension beyond the hour granted. To this day, there has been no resolution as to what caused this discrepancy in timing.

Without direct air support–no artillery and no weapons–and completely outnumbered by Castro’s forces, members of the Brigade either surrendered or returned to the turquoise water from which they had come.

Two American destroyers attempted to move into the Bay of Pigs to evacuate these members, but gunfire from Cuban forces made that impossible.

In the following days, US entities continued to monitor the waters surrounding the bay in search of survivors, with only a handful being rescued. A few members of the Brigade managed to escape and went into hiding, but soon surrendered due to a lack of food and water. When all was said and done, more than seventy-five percent of Brigade 2506 ended up in Cuban prisons.

Wondering what became of the imprisoned members of Brigade 2506? Read The Negotiator, part two of our Bay of Pigs series, to find out how American attorney James Donovan spent months in one-on-one negotiations with Fidel Castro over the fate of those 1,113 Brigade members.