The 1950s and ‘60s were a time of great change in the United States. With civil rights coming into focus and the institution of segregation being dismantled, opportunities for black Americans to move into predominantly white sectors increased. Many of these opportunities, however, came with the challenge of being “first,” and for many black Americans, being first also meant being “the only.”

As George E. Hocker, Jr. embarked on his career with CIA, he was very aware of needing to serve as a role model when it was his turn to be “first.” Among his many “firsts,” George has the distinction of being the first black officer to open an overseas station and the first black officer to become a branch chief in the Directorate of Operations (DO).

George E. Hocker, Jr. with former CIA Directors George Tenet (left) and John Brennan (right) in 2020.

* * * * *

George was born in 1939 and grew up in Washington, D.C. It was not until 1953 that President Eisenhower desegregated the nation’s capital as a model for other U.S. cities to follow. As the oldest of five children, George was a natural role model. His parents always taught him to respond to prejudice with personal integrity and they emphasized education, telling him, “If you don’t finish high school, the rest (of your siblings) won’t finish high school. If you don’t go to a college, the rest won’t finish college.”

He enrolled at Howard University in 1956, and while attending, his close friend convinced him to apply to the CIA. At 18 years old and with no real work experience, George used his parents’ church friends as references on his application. The Agency came calling, and he entered on duty in 1957 as one of a small number of black officers. CIA Trailblazers Don Cryer and Omego Ware were among his contemporaries.

George’s job offer letter from CIA in 1957.

Upon entry, George encountered the reality of an organization composed of mostly white officers drawn from Ivy League schools. A few years into his CIA career, he also experienced being passed over for sponsorships and promotions that favored his white colleagues.

Doing the work as an analyst at Headquarters and seeing what was coming in from the field, he became intrigued with the idea of collecting intelligence as a case officer. According to George, “There was this scuttlebutt going around the Agency that blacks could not be spies because they would stand out anywhere in the world… The lightbulb went off for me and a couple of my friends—if anybody were to stand out in the world, it’s going to be white guys because 90-plus percent of the world are people of color, some kind of color. I had decided that I was going to break this mold of people saying blacks couldn’t be spies—we can do this, and the world needs us.”

George and the March on Washington

George knew deep down that he should join the well-publicized “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” that took place in his hometown of Washington, D.C. on August 28, 1963. What he didn’t know at the time was that attending the event would become a defining moment in his life.

Image of button from the March on Washington in 1963. [Photo from George Hocker’s private collection.]

George squeezed through the masses of people to get within 100 yards from where Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech. It was the first time George had seen so many people lining both sides of Constitution Avenue. The whole area was packed with a few hundred thousand people—blacks and whites together. As people wiggled around and bumped into each other, George recalled stepping on a white man’s foot, prompting the man to say “Excuse me,” first. Those gathered remained peaceful to ensure the event was a success.

View of participants of March on Washington on August 28, 1963. [Photos from Library of Congress and National Archives.]

To George, the memory of the march and the crowds that day remained vivid. “I saw that we can do some things together, all races, if we can come together and if we can strive to be the best that we can be and help our country to be the best example for the rest of the world.”

In the mid-1960s, George pursued his dream of becoming a case officer. The covert operations training program, however, was a difficult time for him. A lot of men there were prejudiced and didn’t talk to him. The only blacks around were those serving the trainees and cleaning up their rooms.

George wound up being the first black officer to undertake months-long escape and evasion training as part of the program. His skill, determination, and intrinsic resilience carried him through graduation, and he went on to serve multiple tours across Africa and South America. In each assignment, he executed the mission with excellence, demonstrating how racial diversity enables CIA’s operational success overseas.

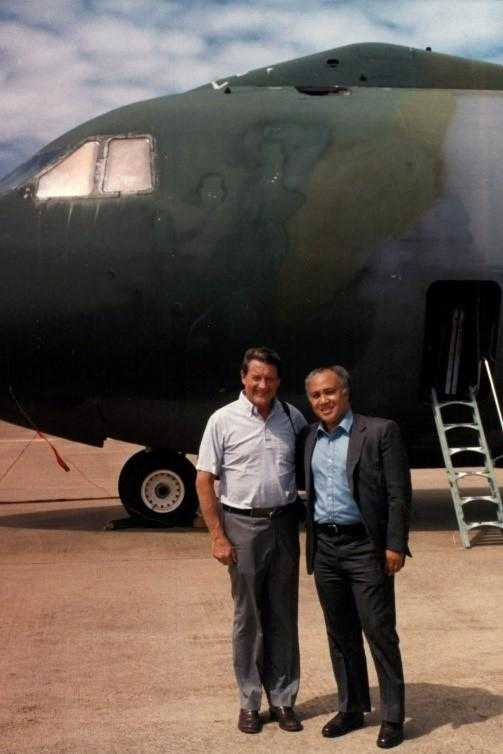

George Hocker (right) with former CIA Director William Webster.

Overcoming racial discrimination was a constant hurdle for George. Barriers to advancement took many forms from personal bias that prevented timely career advancement to inequitably applied rules that delayed professional opportunities. Confident in what he had to offer the Agency, he was willing to question the system and those in leadership roles to ensure fair treatment. This was never a comfortable or easy position.

George’s distinguished CIA career highlights include serving as the first black officer to open a new CIA station and the first black branch chief within the DO. He was also selected to serve as the special assistant for Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Stansfield Turner and DCI William Casey and as Senior Advisor to the Drug Enforcement Agency—a role he held until his retirement in 1992.

George Hocker with Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Stansfield Turner (top) and DCI William Casey (bottom). Both directors signed photos offering their thanks and well-wishes to George for his service.

“I don’t have anything but great praise for the overall work of the CIA and officers who put their lives on the line every day, especially those overseas serving in difficult situations,” he said. “I will always have regret for officers who were lost (including) one of my closest friends—and I only had a handful of close friends in my case officer training—a guy named Mike Maloney... I also lost the deputy that I had in Beirut, Lebanon. Those are tough things. I know that the men and women of the Agency serve a higher cause.”

George recently returned to CIA Headquarters to highlight key moments in the Agency’s history and offer advice to the next generation of officers. “I still feel very privileged and honored to have been able to serve my country as a black spymaster and be in the CIA for 34 years. I think it’s very important for you to be able to be resilient and persevere when things don’t seem to be going your way, especially if you think they’re unjust… If you don’t stand up for yourself, sometimes you won’t be the value to the Agency that you should be.”

Pictured here is CIA Museum’s exhibit within the corridors of Headquarters, highlighting the career of George Hocker, Jr. Some of the items on display include photos, letters and awards, and mementos from locations where George served.