1986 was a momentous year in the United States. The country wept as the space shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff with seven crewmembers aboard, including teacher Christa McAuliffe, the first ordinary American set to travel into space. More than 6 million people formed a human chain stretching from New York City to California with the “Hands Across America” campaign to raise money to fight hunger and homelessness. And, Top Gun—the highest grossing film that year—boosted U.S. Navy recruitment.

It was also the year that Brigitte, a young lady whose ancestors were of Blackfeet Nation Native American heritage, joined CIA. She started out as a GS-04 security escort. For Brigitte, who grew up in Northern Virginia and had been working for her dad painting houses, making $6.16 per hour at CIA was a boost in pay that also included benefits, so she was happy about that.

The Role of Strong Women

Early on in her career, Brigitte joined CIA’s Security Protective Services, the security force with federal law enforcement authority charged with protecting Agency personnel, facilities, and information. Like all Security Protective Officers (or SPOs as they are commonly called at CIA), Brigitte received specialized training in Georgia, where she mastered such skills as highway response driving and sharp shooting.

Brigitte’s photo featured on a brochure to support Security Protective Services’ recruiting efforts, circa mid-1980s.

Check out episode 009 of our podcast, “The Langley Files,” to learn more about the Security Protective Officers who keep CIA personnel and facilities safe.

Brigitte’s next assignment introduced her to a love of technology, an area she ended up spending most of her Agency career. Over the years, she was part of CIA teams that revolutionized the Agency’s information management capabilities from predominantly paper and courier delivery to electronic and real-time delivery.

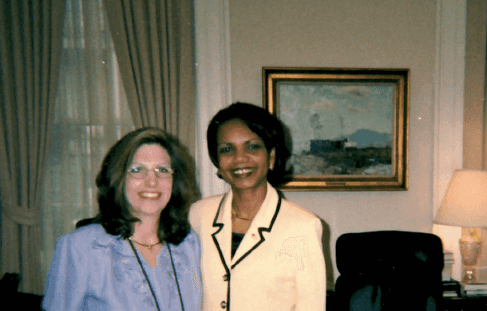

In the 2000s, Brigitte earned the opportunity to participate in U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Executive Leadership Program (ELP), a competitive year-long program designed to prepare federal employees for senior roles. Within the program, she was selected for a 60-day development assignment working for the Executive Office of the President under the second Bush Administration. One day, Brigitte emailed then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to see if she could interview her. Secretary Rice agreed.

Brigitte with then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.

“Secretary Rice was not only inspiring, brilliant, and a trailblazer in many respects, but she was warm and genuine,” recalled Brigitte, looking back at the experience. “She taught me that when we have challenging seasons in life, like her role as Secretary of State working long hours 7 days a week, it is important to prioritize things. For instance, she prioritized church and a fun activity on Sundays. Ms. Rice once told me, ‘Boundaries are important to maintain control and stability in life.’”

Within the USDA program, Brigitte also had a week-long shadowing assignment with a CIA division chief named Jeanne, who would later head the Directorate of Support. Brigitte worked for Jeanne after graduating from ELP. Jeanne was not only Brigitte’s mentor, but a role model who she aspired to emulate. Jeanne listened to her. Believed in her. “Having someone like Jeanne in my corner motivated me to work harder and be more creative and tenacious in solving problems. I will always tremendously admire Jeanne, and I am deeply appreciative to have served under her leadership.”

Keeping Heritage Alive

Brigitte has been a longtime member of CIA’s Council of American Indians and Alaskan Natives (CAIAN) Agency Resource Group (ARG) that works with partners to represent American Indian and Alaskan Native officers, eliminate impediments that restrict Native officers from joining CIA and using their diverse talents to serve the Agency’s mission to their full potential, and contribute to an overall positive and inclusive workplace at CIA. She has participated in Agency-hosted events throughout her career and enjoys constantly learning about and sharing various aspects of Native American cultures and traditions.

Brigitte participating in a presentation by Will Hill (left), a traditional storyteller born of the Nogonugojeeh (Storytelling Society) of the Muskogean people, at CIA Headquarters. On the right, Brigitte sharing information about Native American heritage with officers at CIA.

During one of Brigitte’s assignments, the group created talking sticks for each CIA Directorate to share the importance of inclusion, listening, and respecting the ‘sacred point of view’ that each member brings to meetings. The talking stick is used in many Native American traditions when a council meeting is called to discuss matters of importance to the tribe. The elder in charge holds the talking stick as a signal that the meeting is about to begin, and the stick is passed around the circle to give each person the opportunity to speak. Only the person holding the stick may speak while attendees listen closely. Native Americans believe that all present at the meeting deserve an opportunity to speak and be heard.

Brigitte’s talking stick ‘Spirit Prayer.’

In indigenous cultures, the materials and ornamentation of every talking stick carries symbolic meaning. For instance, Brigitte—inspired by the significance of the CIA Directorates’ talking sticks to create her own—made ‘spirit prayer’ with aspen wood to give a meeting clarity of purpose, rabbit fur to aid in listening to all perspectives, blue jay feathers to bring intelligence and guidance, buck skin for grace and survival, black for focus and success, white for purity and spirit, and blue for wisdom and prayer.

Want to learn more about the importance of CAIAN and how CIA’s ARGs provide a safe space and sense of community for our officers? Watch “A Conversation with the Council of American Indians and Alaskan Natives.”

Shattering the Glass Ceiling

“Many years ago, I remember reading about the ‘Glass Ceiling,’ which was an invisible barrier preventing women from advancing to the top of their career fields. I thought I would be lucky to be promoted and retire at the GS-12 level someday,” Brigitte shared. “However, women before me at the CIA blazed a trail for equality in advancement opportunities, and I worked hard leaving positions better than I found them. In the later part of my career, I was proud to advance as a senior GS-15. The shift in CIA’s culture did not happen overnight, and I would not say that we have reached utopia, but we have come a long way in leveling the playing field.”

“After 36 years of honorable service, I recently retired. I believe my work has made a difference to the Agency, to individuals, and to our nation. I believe CIA is vital to the security and freedoms we enjoy as Americans. Our work will never be done; we, as intelligence officers, must all press on.”