“I think we should think of the CIA as a national asset that must be preserved as a vital part of our defense system. . . It is important that the American people understand the intricate job the CIA is doing in an increasingly complex world. It is essential we have the support of the American People.”

— George H.W. Bush, speech in San Antonio, Texas, 1978

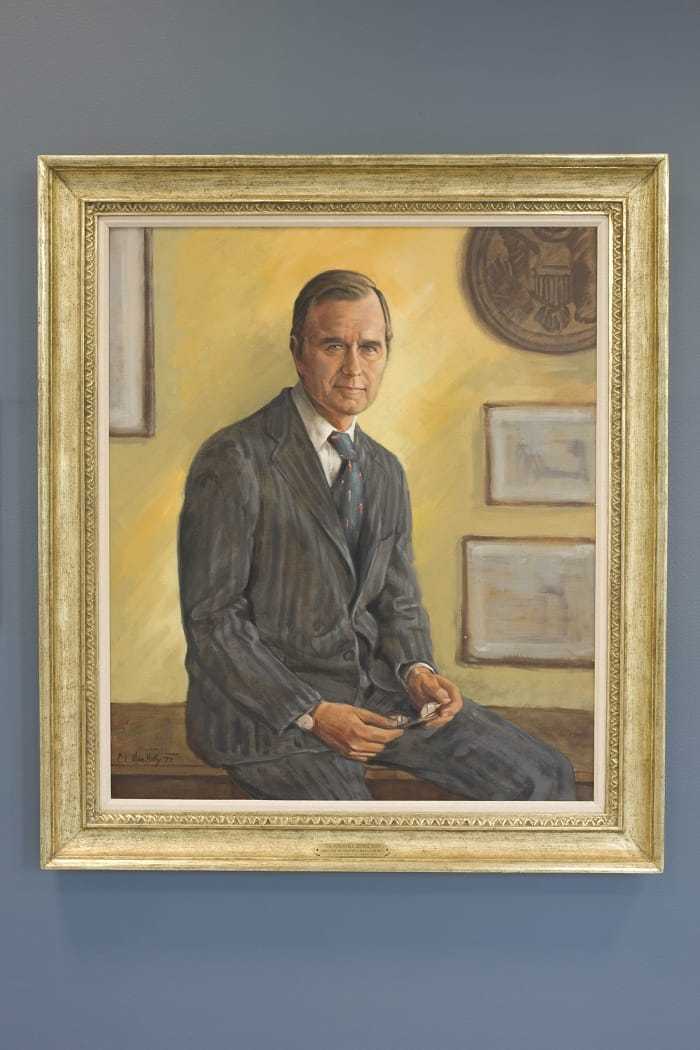

George H.W. Bush’s tenure as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) marked a turning point for the Agency as it came out of a period of great controversy. He is credited with restoring focus and boosting morale, and he remains one of the most beloved directors in the Agency’s history.

An Agency on the Brink

The turbulent 1970s came to be known as the “time of troubles” for the CIA. Six different DCIs served within a ten-year timeframe, and the Agency was shrouded in controversy from the Vietnam War and covert action programs leaked to the press.

By far the most devastating and consequential leak involved the “Family Jewels,” a list compiled for DCI James Schlesinger detailing controversial and, in some cases, illegal activities undertaken by the Agency. By December of 1974, the list had ended up in the hands of investigative journalist Seymour Hersh.

President Gerald R. Ford sought to quell public and congressional concern by establishing a blue-ribbon commission led by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller to investigate any domestic espionage by the Agency.

Congressional committees led by Representative Otis Pike and Senator Frank Church were formed in early 1975 and aimed to expunge the questionable activities of the CIA in the 1970s. Church referred to the CIA as a “rogue elephant,” claiming it was unsupervised and designed to tell the President what he wanted to hear.

Neither committee discovered evidence capable of destroying the Agency, although the hearings decimated the public image of the CIA and the pride of its employees.

As the committees continued their investigations into late 1975, the Ford Administration had come to feel that then-DCI William Colby had disclosed more information to Congress than was necessary. This belief, coupled with the harsh reality that a dark cloud now hung over the CIA, led the President to conclude the Agency needed a new sense of morale and a new director who could improve strained relations with Congress. On January 30, 1976, Ford replaced Colby with George H.W. Bush.

A Career Politician

“[CIA employees] had every reason to be suspicious of this untutored outsider who. . . had spent a lot of time in partisan politics. . .But this Agency gave me their trust from day one.”

— George H.W. Bush, remarks at CIA HQs, 1999

As a Texas Congressman, National Chairman of the Republican National Committee, Ambassador to the UN, and Special Envoy to China, George Bush had established a reputation as a strong leader with an impressive resume. Ford had even considered appointing Bush as his Vice-President, but instead offered him the job of DCI. Bush privately feared the position would end his political career but wrote to his family that he had accepted because of a strong obligation to his country and his president.

Bush was sworn-in on January 30, 1976 and immediately began establishing himself as a leader who would restore the morale and reputation of the CIA.

Despite being new to the Agency, he quickly identified with CIA’s workforce. At one of his first meetings as DCI, he held up a folded newspaper and asked the surrounding group of officers, “You see what they are doing to us?” Other Agency personnel quickly witnessed the friendly and outgoing persona of Bush. The new director was always interested in meeting them and hearing their ideas and opinions.

Access to the President

“One of my continuing concerns has been that with the prevailing sensationalism in stories about the Central Intelligence Agency, much of the essential work of that agency—work that is vital to our national defense and or national interests—has been largely ignored.”

— George H.W. Bush, speech in Pasadena, Texas, 1977

While Special Envoy to China, Bush was frustrated by the amount of power Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wielded in determining and assessing policy. As a result, when Bush became the new DCI, he insisted upon direct access to President Ford.

Ford became the first president to be briefed everyday by an Agency officer, but he had decided to allow National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft to review the President’s Daily Brief (PDB) with him, instead of CIA, while Colby was still DCI.

Bush usually edited the PDB or briefed National Security Council (NSC) meetings in order to convey his analysis to the President.

Nevertheless, Bush and Kissinger continued to clash over intelligence reports concerning Soviet capabilities and threats. Specifically, CIA estimates indicated the USSR was moving more aggressively beyond a policy of nuclear deterrence; a conclusion that threatened to undermine the détente policy Kissinger had staked his career and legacy on.

In February, 1976, the President issued executive orders 11905 and 11906. The first ordered the CIA to limit its domestic surveillance. The second established a three member Intelligence Oversight Board (IOB) to examine possible illegal activity within the Intelligence Community (IC).

Bush accepted these changes and enforced them.

A news conference was held on February 17th, during which President Ford informed the nation that he expected three units to oversee the entire IC: The NSC, the IOB, and the newly-created Committee on Foreign Intelligence, which was chaired by Bush himself.

Ford included Bush in significant meetings, such as an emergency NSC meeting following the assassination of US Ambassador Francis Meloy in Beirut on June 16, 1976. Bush provided intelligence on ideal escape routes for Americans fleeing the troubled country. For their regular briefings, Bush brought Agency officers to meet and brief with Ford, a tactic that impressed the President and contributed to the morale boost at Langley.

Changing the Dynamic with Congress

As one important goal of his directorship, Bush sought to improve relations between the Agency and Capitol Hill in the wake of the Pike and Church Committees. Being a former member of the House of Representatives, Bush had the ideal background for reconciling the hostility between the two organizations. One clever strategy he employed was arranging a series of dinners at his home, which were attended by CIA officers and Senator Church.

The challenge of repairing relations coincided with efforts to expand the role of Congress in overseeing the CIA. In July 1976, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) went into operation. The SSCI comprised fifteen senators, including the leaders of both parties, and was specifically intended to provide more permanent oversight of the Agency and review the overall budget of the IC.

DCI Bush embraced the SSCI and soon thereafter gave its members a comprehensive briefing of CIA covert action programs. Agency officials also educated SSCI members about intelligence collection and production. Bush himself would return to testify before Congress on fifty-one separate occasions during his year in office, setting a record no other DCI has matched.

To keep Congress better informed, Bush discontinued the production of the daily Congressional Checklist in favor of sending copies of the more inclusive National Intelligence Daily (NID), the predecessor to today’s World Intelligence Review (WIRe). Due to the highly classified nature of the NID, access to the publication was limited on Capitol Hill and all copies had to be returned to the Agency at the end of each day.

Briefing Jimmy Carter

“I was very honored to have President (then DCI) Bush come to brief me. President Ford offered every assistance.”

— President Jimmy Carter, 1993

By June of 1976, Governor Jimmy Carter took the unprecedented step of asking for CIA briefings even before he was officially nominated as his party’s candidate for President.

Bush first met with Carter to discuss ground rules on July 5th in Hershey, Pennsylvania. After Carter was officially nominated, Bush presided over more detailed briefings. The CIA’s briefings for Carter were aimed at helping him understand the workings of the IC, as well as to process the classified information he was being given. Briefers appealed to his business instincts by discussing the finances of the Agency and using economic metaphors to explain key points.

Carter was inquisitive and eager to learn about intelligence activities, and the DCI brought eight other officers with him to every briefing to ensure every question asked could be answered. For Bush, the hardest part of the process was navigating his way to Carter’s home in Plains, Georgia. Since he could not land the Director’s plane in Plains’ dirt airfield, Bush flew into Fort Benning then flew by helicopter to see Carter.

The CIA briefings placed Carter on more equal footing with Ford when discussing foreign affairs during the presidential debates. Carter was so pleased that he even considered keeping Bush on as DCI if he was elected.

However, by Election Day, Carter had decided against it. Three days after Carter’s victory over President Ford, Bush called and offered his resignation. Carter became only the second president to pick a new DCI when he first entered the Presidency, setting a trend for presidents to come.

A final briefing between the two occurred on November 19th, when Bush described more than ten sensitive programs being run by the CIA and even mentioned staying on as Director. Carter was notably quiet. He later shut down many of these programs and accepted Bush’s resignation on January 10, 1977, the day of the Presidential Inauguration.

Farewell for Now

“If I had agreed to [let Bush remain DCI, he] never would have become President. His career would have gone off on a whole different track.”

— President Jimmy Carter, 1993

“I take with me many happy memories. Even the tough, unresolved problems don’t seem so awesome; for they are overshadowed by our successes and by the fact that we do provide the best foreign intelligence in the world. I hope I can find some ways in the years ahead to make the American people understand more fully the greatness that is CIA.”

— George H.W. Bush, DCI Farewell Address, 1977

Although Carter was pleased with reforms made at the CIA, Bush’s ties to the Republican Party made him too political to be retained by the Carter Administration.

Carter eventually selected Navy Admiral Stansfield Turner to be the next DCI. Turner was impressed by Bush’s enthusiasm for the CIA and was told by Bush that the DCI position was “the best job in Washington.”

Bush quietly left Washington and returned to Texas, where he built up support for his campaign to be the Republican nominee for President in 1980. Although he lost to Ronald Reagan, he was elected Vice-President for eight years (1981-1989) and then served a term as President in his own right (1989-1993).

These positions made Bush the only producer (as DCI) and consumer (as President) of intelligence in a single career.

Welcome Home

“Your legacy resonates deeply, even to this day. From your name on the signs marking CIA headquarters, to your advocacy for CIA’s value in an increasingly complex world, to your vision of this Agency as one unit and one family, your tenure left a deep impression. This is your CIA in more than just name. Welcome home.”

— Director John Brennan welcoming Bush back to CIA HQs, January 29, 2016

Although Bush’s tenure was short, it was a meaningful and helpful “calm between the storms” for the Agency in the 1970s. He saw the integrity of a badly-bruised CIA when many in the public and even the government could not. He spoke publicly about the importance of the Agency and even started to mend our relationship with Congress that had been badly damaged. Bush truly loved the job of DCI, a position he considered to be the best in Washington, enough to risk political oblivion to take it.

In 1999, by the order of Congress, the CIA Headquarters compound in Langley, Virginia was renamed the George Bush Center for Intelligence.

A ceremony attended by President and Mrs. Bush and Director and Mrs. Tenet on April 26, 1999, marked the official naming of the CIA compound. Bush was honored for his life’s work as a public servant and for providing a restored sense of morale at the Agency.

During the dedication ceremony, Bush remarked, “So to George Tenet, our great Director and everyone at CIA, all I can say is that the gratitude in my heart literally knows no bounds. I left here some 22 years ago, after a limited tenure, but my stay here had a major impact on me. CIA became part of my heartbeat back then, and it’s never gone away.”

In 2016, in honor of Bush’s tenure as DCI and to mark the 40th anniversary of his swearing-in as Director, the Agency announced the newly-created George H.W. Bush Intelligence Officer award. The award recognizes CIA officers who engage as exceptional partners across the Agency and within the IC; who strive to deepen tradecraft and expertise; and who deliver on mission, to include how we can improve our performance.

Bush returned home to the Agency for the occasion and to present the awards.

“It is a great joy for me to return to a place that means so much to the defense and security of America,” said Bush in a statement to the Agency. “To be honest, I am not sure what impact I had on the CIA during my fascinating year helping to lead the Agency, but I can tell you the men and women there made a lasting and profound impact on me… They never get the full recognition they deserve, but it did this 91-year-old heart good today to try to express to them the thanks the men and women of the CIA are surely due.”