Dear Molly,

I’m working on my spy novel for National Novel Writing Month. Do you have any suggestions for how I can make my writing sound more like a real spy?

~ Secret Scribe

* * * * *

Dear Secret Scribe,

Congratulations on your spy novel! Did you know that many spies, even some famous ones, have tried their hand at writing fiction? Even Ian Fleming, the creator of what is arguably the most famous fictional spy in history, James Bond, served as a British Naval intelligence officer during World War II.

My first suggestion is to read, read, read! Check out as many books and articles as you can to learn more about the intelligence profession, as well as books or novels written by intelligence officers. If you want some insider recommendations, check out “The Intelligence Officer’s Bookshelf” section of Studies in Intelligence. That’s where I always find my next great read!

As for unique tips, I do have a few CIA-specific resources I can recommend.

First, brush up on your spy lingo! Check out our Spy Speak Glossary, which contains a lexicon of words and phrases used in the intelligence profession. Next, definitely take a look at a recent article on colloquialisms used by CIA officers at Langley. And lastly, I have to put in a plug for our News and Stories section on CIA.gov, where you can learn more about real-life spies and their daring adventures. Perhaps this could help inspire fresh ideas for plots and characters in your novel.

Next, I thought you might find some actual CIA writing tips and advice useful. At the Agency, we write. A LOT. Whether it’s analysts writing reports at Headquarters, ops officers writing cables from the field, or historians writing complex histories for Agency records, all CIA officers find themselves as scribes at some point during their daily duties.

| “The pen is sometimes flightier than the words.” |

| – From a 1994 DO Writing Guide |

Here are five writing tips I gathered from across the Agency I thought you might find useful:

Top Five CIA Writing Tips:

- BLUF – Bottom Line Up Front: Readers are busy, so you want to draw them in immediately and give them the most important information at the beginning. In intelligence writing, we call this the “bluf.” If your audience only reads the first sentence or two, you want them to come away with your best insights and conclusions. In fiction or narrative non-fiction writing, use the same idea for an impactful start by creating a compelling introduction, where you draw the reader into your story with a fascinating anecdote, quote, or scene.

- Avoid Jargon and Ornate Language: The spying world is full of acronyms and jargon. Although it might be tempting to use all the spy lingo you can find, it’s better to sprinkle it into your story strategically, and be sure to explain what any words or phrases not familiar to an everyday audience mean. If you have the option to use a simpler word or phrase with similar meaning, do it.

- Vary Structure and Length of Sentences and Paragraphs: Good writing has a rhythm, almost like music. And like music, if the notes and melodies never change, it becomes monotone. Static noise. By mixing long and short sentences, and playing with the structure of paragraphs, you can create a compelling cadence to your words.

- Double-Check Frequently Misused or Confused Words: This is where the Spy Glossary (and a dictionary) can come in handy.

- Avoid Imprecise and Vague Language: Sloppy language can lead to misunderstandings, which as an intelligence officer, you obviously want to avoid. For a novelist, it can make your prose confusing, or worse yet, boring. Keep language crisp, clear, and direct.

| “Good intelligence depends in large measure on clear, concise writing. The information CIA gathers and the analysis it produces mean little if we cannot convey them effectively.” |

| – Introduction to CIA’s Style Manual and Writers Guide for Intelligence Publications, eighth edition |

Remember, it’s okay to break writing rules, as long as you know what the rule is and are consistent about breaking it. As an old CIA Historian’s writing guide says, “This manual is not intended to be [a] straitjacket but [a] guide; its rules may be broken for almost any reason except negligence. Once the writer has broken a rule, however, he [or she] has in effect written a new rule, which he [or she] is under obligation to follow consistently.”

Another thing you might consider is the use of visuals to help you tell your story. In intelligence work, we often use videos, graphics, charts, maps, photographs, or interactive visuals to help inform our policymakers. Perhaps you can jazz up your story with visual elements!

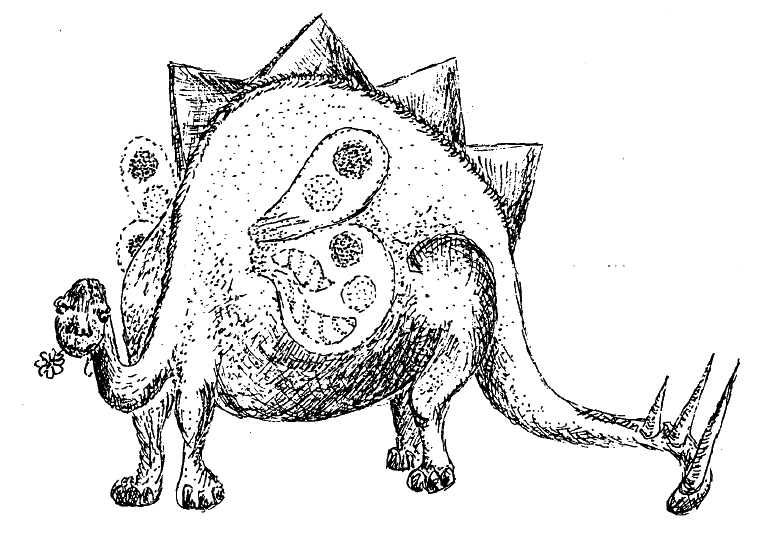

Speaking of visuals, I’d be remiss if I didn’t share with you the oddest (and my personal favorite) collection of CIA writing advice that I stumbled across: “The Bestiary of Intelligence Writing.” In the 1980s, a clever and creative CIA editor had some fun collecting, “specimen samples of cliches and misused or overused word combinations that CIA editors have encountered frequently over the years.”

The author, however, imagined each phase as an absurdist mythical beast—complete with actual sketches of the beasts—to poke fun at the use of the offending phrases in intelligence writing. They wrote about each phrase like it was a creature being described in a naturalist’s journal. The collection includes “beasts” such as multidisciplinary analysis, parameters, dire straits, almost inevitable, and nonstarter, to name only a few.

Here’s one of my favorite creatures, Mounting Crises:

“Mounting crises are frequently detected by intelligence analysts, but genuine crises are rare, and most sightings probably are of the larval form, known as problems and difficulties. Most crises are of the political or economic gender, but occasionally the sighting of a military (or of an even rarer, social) crisis is claimed. Crises tend to shun each other’s company, although political and economic crises sometimes go hand in hand. Because they are almost impossible to identify when young and grow slowly, crises are almost always seen as mounting. They are never observed dismounting, and their decrease remains an enigma to analysts. There is considerable non-scientific thinking about how they end their days: some believe that crises disappear, dissolve, evaporate, or ‘are resolved.’”

Drawing of “Mounting Crises” from “The Bestiary of Intelligence Writing,” 1982.

Even intelligence writing can be creative!

I hope these tips and insights from the world of espionage gave you some inspiration. Good luck with your spy novel!

~ Molly

P.S. The writing tip I’ve found most useful throughout my career: find a good editor. <wink>

#AskMollyHale