“In his day, Jim was recognized as the dominant counterintelligence figure in the non-Communist world.”

Director of Central Intelligence

Richard Helms

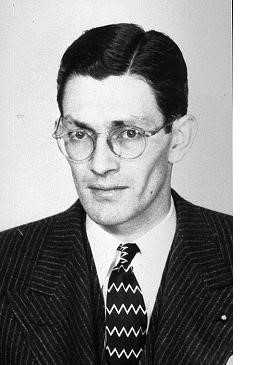

Over the years, many great men and women have devoted their careers to the mission of the Central Intelligence Agency. Perhaps one of the most well-known Agency figures is James Angleton. In particular, Angleton was noted for his work as the Chief of Counterintelligence during the Cold War.

James Angleton

James Angleton was born in Boise, Idaho, on December 9, 1917. His parents—James Hugh Angleton and Carmen Mercedes Moreno—met when his father was serving as a cavalry officer during the Mexican Revolution. Angleton had two younger sisters and a brother.

Throughout his youth, Angleton was educated at English preparatory schools, including Chartridge Hill House in Buckinghamshire, England. He attended Malvern College in Worcestershire, England, but left in 1936 to study at Yale.

During his time at Yale, Angleton took an interest in literature and poetry and edited the school’s literary magazine “Furioso,” which published poetry by the likes of E. E. Cummings and Ezra Pound.

Angleton graduated from Yale in 1941 and enrolled at Harvard Law School.

War Effort

Angleton did not finish law school because he was drafted into the U.S. Army in March 1943. During training he was singled out for an interview and offered the chance to work with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—the predecessor to today’s CIA.

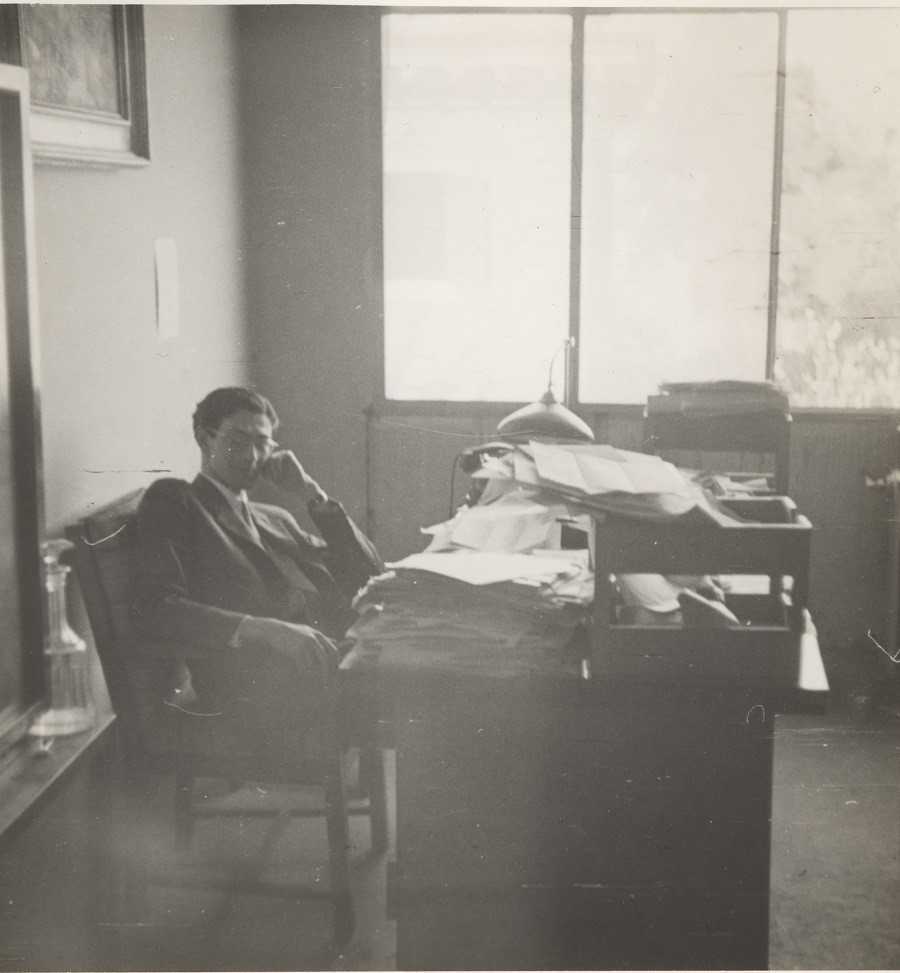

Angleton accepted the opportunity and was assigned to the X-2 Branch, responsible for counterintelligence. Given his knowledge of the Italian language and culture, Angleton began at the Italian desk in Washington, D.C. He quickly grew restless, so he approached the head of X-2, James Murphy, and requested an assignment overseas. Murphy was so impressed with Angleton that he agreed and sent him to England.

Right away, Angleton proved himself to be a hard worker, often sleeping on a cot in his office after working late into the night. Six months after joining the OSS, Angleton became the X-2 chief of the Italian desk in Washington, D.C. In late 1944 he transferred to Rome and, at the age of 27, became the chief of X-2 in Italy.

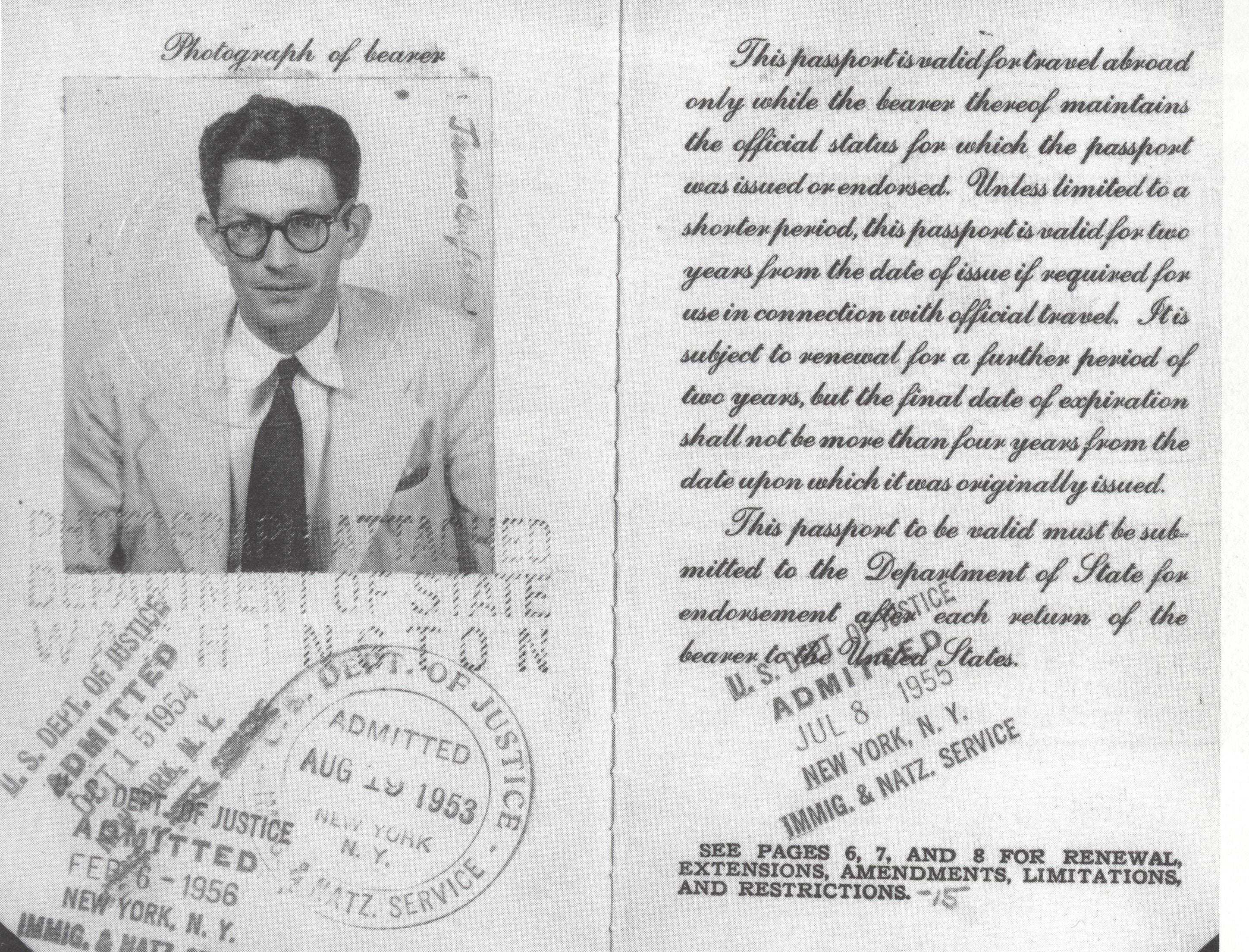

After the war, Angleton remained in Italy and established contacts with other secret intelligence agencies that proved useful later in his career at the Agency. Angleton also played a major role in operations that supported the 1948 Italian general election.

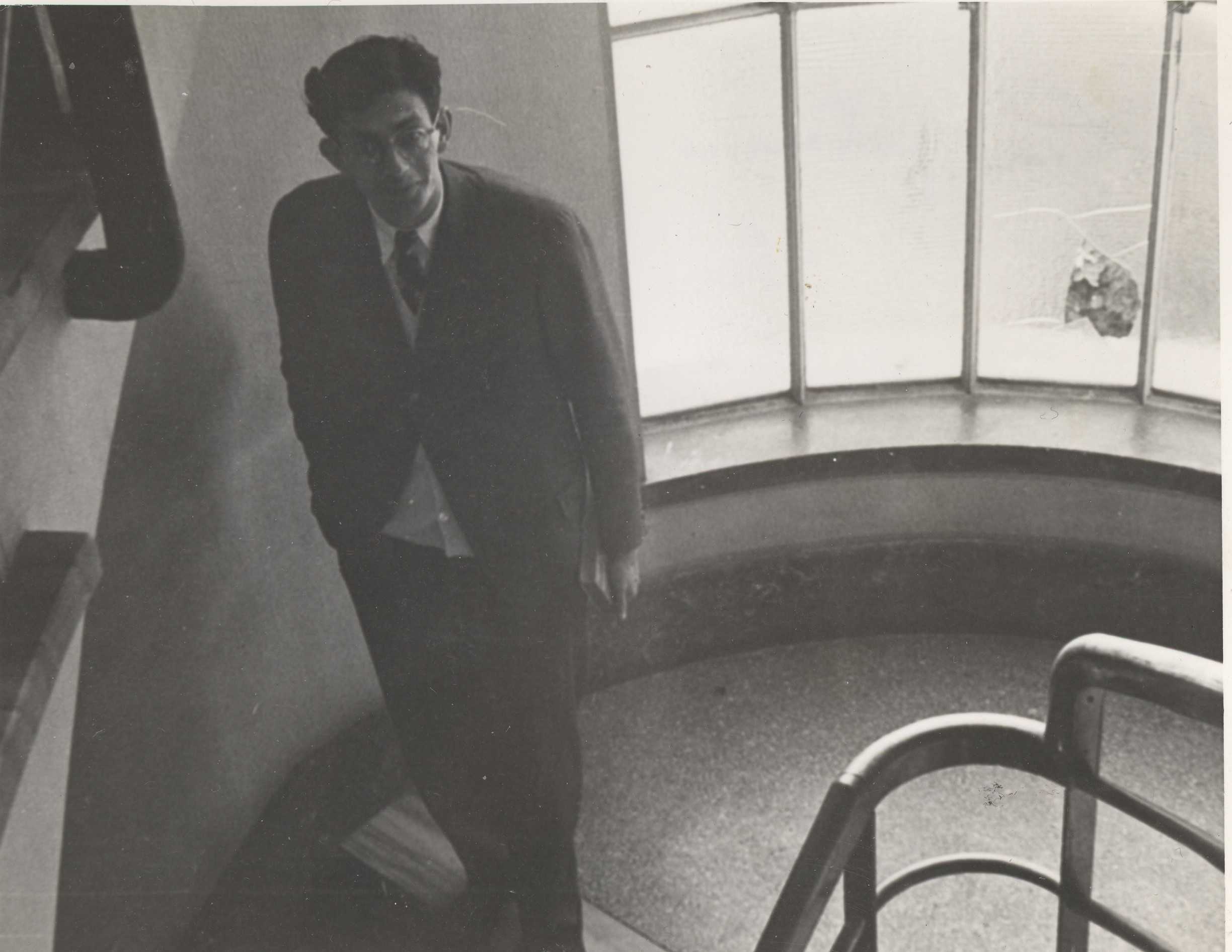

Upon his return to Washington, Angleton worked for various successor organizations of the OSS until the CIA was established in 1947. Angleton made the transition to an Agency employee and is known as one of the founding officers.

Agency Career

During the first several years of his career at the Agency, Angleton helped establish the structure of the new intelligence organization. Living up to his reputation in the OSS, Angleton rapidly rose through the ranks of the Agency.

By May 1949, he became a senior leader in the Office of Special Operations. This job required Angleton to call on some of the contacts he made after the war. Angleton’s relationships with Israel’s Mossad and Shin Bet agencies became especially important during his time working the Israeli desk and throughout his career at the Agency.

In 1954, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Allen Dulles asked Angleton to become head of the Counterintelligence Staff. Angleton remained in this position for the rest of his career at the Agency.

Angleton’s relationship with the Israelis paid off when the Shin Bet provided him a transcript of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s confidential 1956 speech denouncing his predecessor, Joseph Stalin. The speech proved valuable because it showed that Soviet leaders were in the midst of a power struggle. The Eisenhower administration publicized the speech, embarrassing the Soviet government.

Angleton also was involved with debriefing two famous KGB defectors: Anatoly Golitsyn and Yuri Nosenko. In 1961, KGB Maj. Anatoly Golitsyn defected to the United States and was interviewed by Angleton. Angleton found Golitsyn to be a source of accurate information. Golitsyn claimed that the CIA had been infiltrated by the KGB. He also said that another defector would be sent to discredit his information and support the mole’s credibility. Angleton believed Golitsyn and began a mole hunt inside the Agency.

KGB officer Yuri Nosenko made contact with the CIA in 1962, but was not heard from again until 1964 when he defected. During his debriefing, he provided information that contradicted intelligence gathered from Golitsyn’s interviews. Because Angleton declared Golitysn a genuine source, he concluded that Nosenko was a false defector who couldn’t be believed.

Angleton holding the ashes of DCI Allen Dulles.

After President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, the U.S. government briefly suspected that the Soviet Union might have perpetrated the crime. During Nosenko’s debriefing, he made a startling disclosure: he had been assigned to watch assassin Lee Harvey Oswald when Oswald defected to the Soviet Union (1959-1962). Nosenko said the KGB declined to work with Oswald after determining he was unstable.

Nosenko’s surprise decision to defect to the United States and his news that Oswald was not a KGB asset seemed too convenient for Angleton and other Agency officials. Moreover, Nosenko contradicted Golitsyn, Angleton’s key source on the KGB.

Golitsyn claimed that Nosenko was a disinformation agent sent both to discredit him and to hide Moscow’s hand in President Kennedy’s death. A few years later, the CIA decided that Nosenko was telling the truth, but Angleton never changed his mind.

Angleton left the Agency in December 1974. He died of lung cancer 12 years later on May 12, 1987.